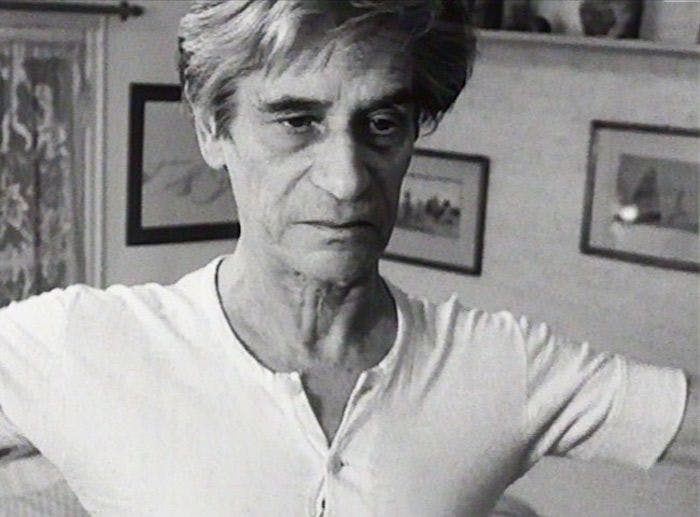

In the little-screened documentary Babilée 91 (1992), about enfant terrible dancer Jean Babilée, the New York–born, France-based director William Klein pulls out all the stops to quickly introduce his audience to a titan of French ballet. By this point in his career, Klein had been an abstract artist, a world-famous fashion photographer for Vogue (considered by some as one of the most influential photographers of all time), as well as an acclaimed fiction and documentary filmmaker with more than a dozen works under his belt. Used to spending years with his subjects, he knew what time does to a body and a body of work. For the documentary Muhammad Ali: The Greatest (1974), he filmed the boxer over a decade. He sent up the French fashion industry twice, 20 years apart: once in 1966’s Who Are You, Polly Maggoo? and then again in 1984’s Mode in France.

He begins his late-career film on Babilée with a montage of the dancer’s daring feats of modernist choreography in movies and in front of live audiences, the man seeming to become lightning while thrusting through the black space of the stage. But the most electric moment in this documentary occurs offstage, in a few quiet minutes of domestic repose, as Babilée prepares for his next performance. Captured intimately by Klein’s wide-angle lenses (the filmmaker’s signature device from his days as a fashion photographer), Babilée and his wife, Zapo, talk, smoke, and make dinner in their cramped Paris apartment, living like students. They watch TV together on their bed and eat in a tiny kitchen. Babilée does pull-ups on whatever surfaces the apartment provides, while Klein zooms in on his aged flesh and tensing muscles.

In a body of work replete with firebrands performing the art of activism for rapt crowds, athletes packing each punch with the full weight of their political lives, and people fighting like (and indeed because) their lives depended on it, Klein’s true gift was for finding people at their quietest and most human. Whether by being in the right place at the right time or not giving up on filming until he’d found what he wanted, Klein shot heroes and turned them into people like us—without ever forgetting that the average person couldn’t really relate to superstars like Ali, or John McEnroe, who appears in Klein’s 1982 documentary, The French.

Born in New York City in 1928, Klein joined the U.S. Army in the ’40s, and after being stationed in France, decided to stay there. He would revisit the States frequently for work (as when he made his debut short film, 1958’s Broadway by Light, a proto–pop art collage dispassionately displaying neon marquees and advertisements in Manhattan), but France would remain his home. In an interview with The Guardian in 2012 he complained of the U.S. that “the place is so reactionary it just makes me angry. If I lived there, you wouldn't be interviewing me, I'd be dead from a heart attack by now." There’s plenty in his 1968 dark comedy Mr. Freedom about his negative feelings towards his homeland: the film shows a murderous blowhard American superhero in France who thinks nothing of destroying the entire country for revenge. The only thing Mr. Freedom can relate to in France is the country’s parallel desire to remain an imperial power.

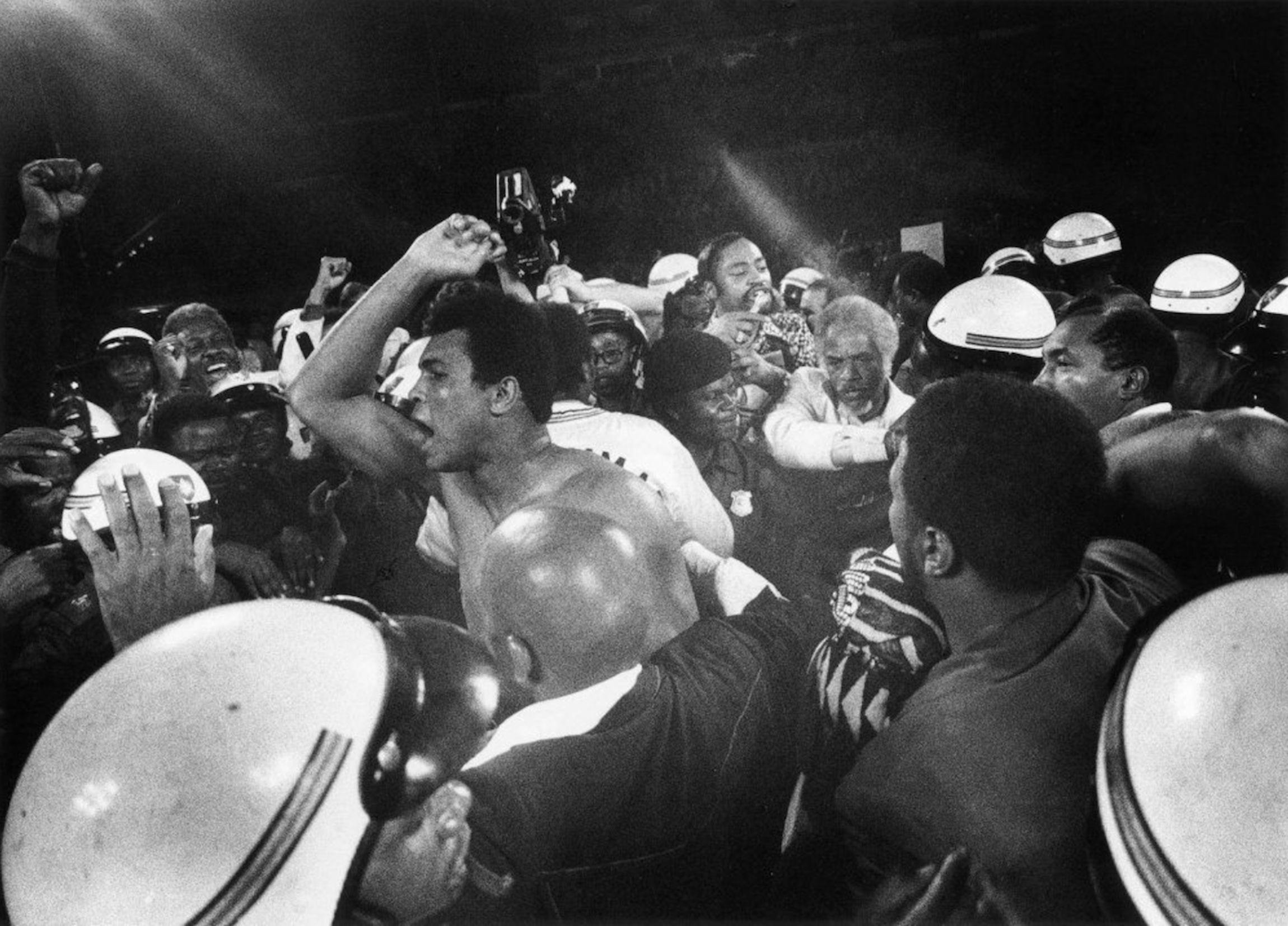

Klein was famous for keeping an ironic remove from his subjects as a photographer. In a 1997 interview, he said, “When I go back and look at my old photographs, I see that black humor was very strong. I've always seen things from a certain distance...” And yet Klein managed to get close to the often guarded subjects of his documentaries. Ali famously played the press like a fiddle, but he seemed to let his guard down in Muhammad Ali: The Greatest—probably because Klein wasn’t interested in the machinery of stardom. He wanted to capture the man without his gloves on; there’s almost no real boxing in the two-hour movie. He just filmed Ali just being himself for years, which must have convinced the boxer that Klein was serious about his humanity, and not just interested in his prowess as an athlete or his magnetism as a polemical figure. Speaking to Forbes Magazine in 2012, Klein said he was hooked when the boxer said of beating Sonny Liston in the boxing world championships, “It feels so good to be able to be bad. Tonight, I was bad.” Ali loses a big match halfway through Klein’s film, which gives its final hour a great hook: can he recover? Klein’s camera, on the other hand, doesn’t seem to care if he wins or loses. It wants to know what the pressures of the upcoming fight are doing to Ali and his entourage. Klein chases a similar intimacy in Eldridge Cleaver, Black Panther (1970), where he got the party leader to open up to him at a time of justifiable paranoia, when Black radicals were under attack from both the American government and the white press. And whether his subjects knew it or not while being filmed, Klein never trimmed or cut short their words; he let everyone have their say. After all, the rambling statements were all part of a performance of the self, and that was Klein’s career-long subject: who we are in front of other people and cameras, and who we are away from it all. He follows backroom meetings in May Days (1978), his portrait of the May ’68 civil unrest in France, and backstage conversations in his films on Ali and Cleaver, trying to unveil the people about whom the whole world had its own ideas.

Muhammad Ali: The Greatest—which had a moment this year thanks to the New York Film Festival’s premiere of a gleaming new restoration—is perhaps the most important film in Klein’s catalog, charting his awakening as a film artist in tandem with Ali’s own spiritual rebirth between 1964 and 1974. It starts with an impressionistic flurry of images and sounds, and indeed the whole first half is an impressive display of Klein’s acuity as a stylist. Rock music plays as Ali, then still known as Cassius Clay, fights his challenger with a million-dollar smile. Klein and his editors, Francine Grubert and Eva Zora, turn Ali’s bout into little bursts of light and sound, as if the movie itself were recoiling from blows to the face. Then the music starts to warp and skip, and just like that, the fight is over. Klein is in the parking lot interviewing the white owners of the Brown-Forman Distilling Company, which sponsored Ali early on, and comprised the “11 Men Behind Cassius Clay,” per a 1963 Sports Illustrated feature on the boxer’s rise to stardom. Klein’s camera woozily considers their faces, distorted again by his wide-angle lens, and looking like grotesques right out of a Fellini film. Klein frames Ali as a live wire surrounded by concerned hands trying to ground him. We see both the white men who claim responsibility for his rise to stardom and the Black men and women who look at him adoringly from the crowd. Ali belonged to everyone, but his biggest fight was to only belong to himself. As the film progresses, Klein stops deploying the editing tricks and starts trying to hone in on Ali’s private behavior. Klein saw someone smarter than everyone around him, itching to prove it, and looking for a world that deserved a man like him.

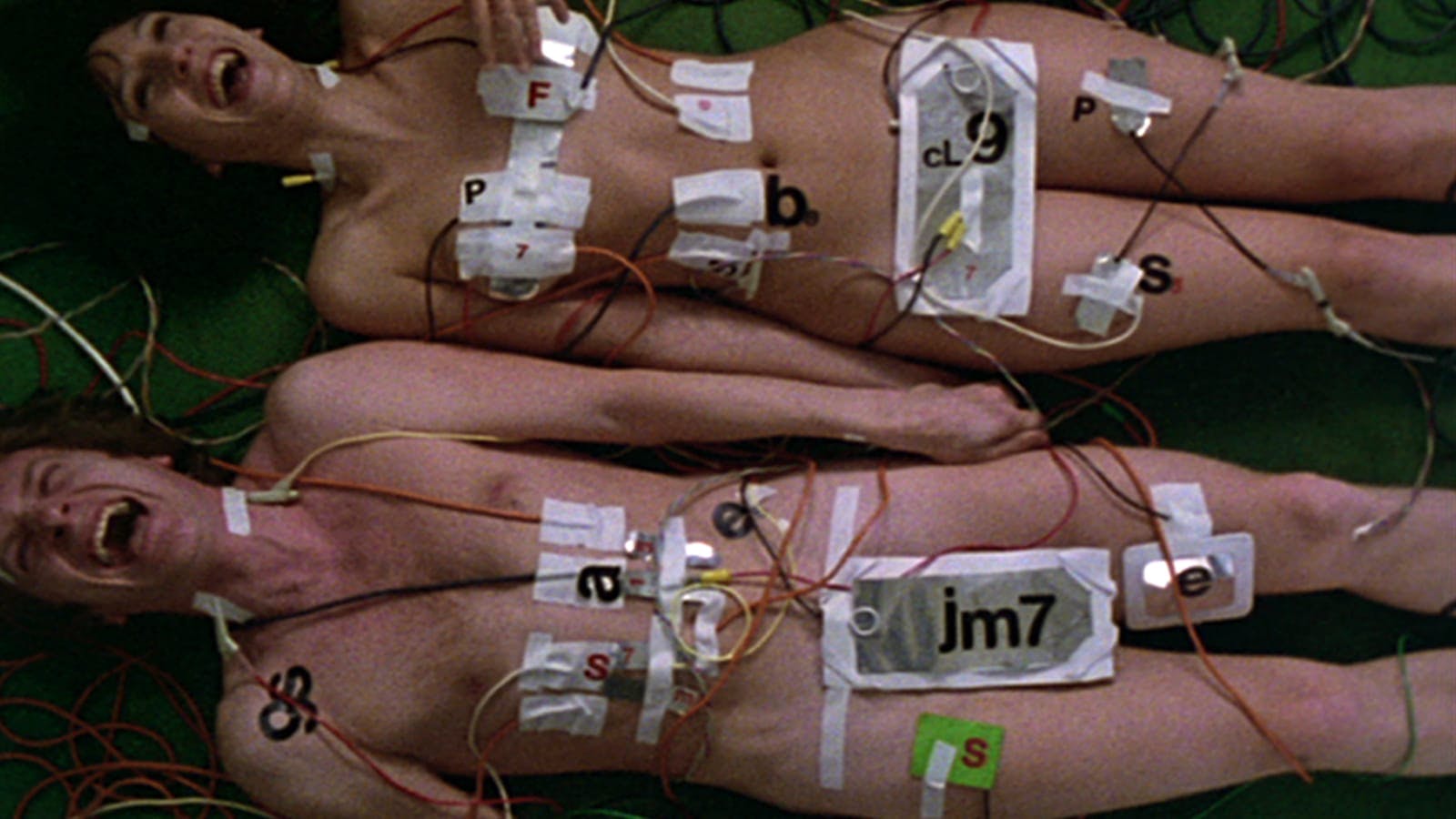

Klein was nobody else’s idea of a filmmaker, which is why his body of work remains so tantalizingly underseen and undigested. His fiction films, with their bitter mockery of politics and pop culture, are better-known: Mr. Freedom is something of a cult film. Who Are You, Polly Maggoo? lampoons the world of fashion photography through the story of an American model in Paris who’s hounded by the press and courted by a prince; 1977’s The Model Couple, about a pair of lovers who agree to be filmed night and day by the government, takes apart the idea of showing yourself off for a living. Those films alone guarantee him a spot in the pantheon of iconoclasts, combining as they do Godardian insouciance and Joe Dante–style pop nihilism.

But Klein’s documentaries remain fairly obscure. They’re hard to categorize and haphazardly screened; some films are out of print, while others were never released. They’re also starkly different from his narrative works: How could the same man be so vehement and vicious in his fiction, and so nonjudgmental and patient in his nonfiction? You watch films named for some of the most famous men of the 20th century and discover that those works aren’t about them at all. They’re about the heroes created by movements, and the movements created by people. At the end of Mode in France, a hybrid nonfiction survey of the fashions of the day through the work of famous French designers, Klein explores the voyeuristic and deeply commercial relationship between celebrity and its consumers with a funny segment in which people throw change into coin-operated televisions that play videos of models talking about their lives. It’s as if they’re trapped inside little boxes, waiting in the dark for an audience.

A brief survey of Klein’s subjects reveals a sort of omnivorousness that repels an easy thematic bead. On the one hand: Ali, Cleaver, anti-colonial struggles in Africa (The Pan-African Festival of Algiers, 1969), May ’68. On the other: Babilée, the 1981 French Open, Parisian high fashion, Little Richard (The Little Richard Story, 1980). But what unites them is Klein’s approach. Like an epidemiologist with a centrifuge, he watches masses of people and waits to see who separates themselves from the rest. In The French, he observes days of matches to see who will emerge victorious, but also who can hold the attention of the camera and the audience. In May Days, he captures perhaps better than any French filmmaker the spirit of that turbulent time and place by flitting from one tense and voluminous meeting of radicals to another, and juxtaposing their debates with footage of the childcare efforts happening in the next room. Klein never picks a hero; instead, in the streets and in backrooms, the throng demands to have its say.

May Days finds its counterpoint in Klein’s best work of nonfiction (and his last film to date), the Ken Russell–esque Messiah (1999), which may be even more despairing than Mr. Freedom. The film captures the various manifestations of religion in America through images of mass baptisms, Christian pro-gun paraphernalia, and T-shirts sporting cheesy religious slogans, all set to Handel’s eponymous composition. Just a few seconds of the homeless going through the trash and a quick drive-by of what was then the Trump Taj Mahal would have made his point, but he maintains a furious hull speed for two hours, piling images of Christians and the people who might benefit from Christian charity on top of each other, underlining that they’re never in the same room. In May Days the fight is over before it starts, by virtue of the film being released 10 years after the events it captures. In Messiah, it’s over because by now there’s too much to fix (gun violence, homelessness, hunger), and too little impetus to fix it.

Klein was always aware that his movies had to be about the hungry public as much as their idols, because a couple of losses too many and those legends become part of the masses once again. In The French, Klein spends several days on the court, getting to know individual players and their styles but not favoring anyone in particular—despite having access to superstars like McEnroe and Björn Borg. What interests him more is how everyone plays and everyone loses. Klein cuts together their defeats back-to-back in a 130-minute marathon. Players lose the most important competitions of their lives every couple of minutes—the repetitive nature of it reveals the highs and lows with which they live. Yes, it’s crushing and agonizing. But this is just life. Ultimately the lynchpin of the whole movie is a scene in which champions Jimmy Connors and Ilie Năstase square off at a charity match, stealing each other’s soft drinks and play-fighting like Laurel and Hardy for an adoring crowd. The Open is just one more rodeo, and the players there are only too happy to be clowns. Like Ali, they can get a laugh out of a crowd as easily as they can stun it speechless with their sporting prowess.

“Don’t tell me I ain’t a perfect specimen of a man!” Ali yells in Muhammad Ali: The Greatest at the journalists assembled to watch him train. He needed to be loved to truly win—to be able to lose to George Foreman and still be “the greatest.” Klein made movies about people who seemed like superheroes, lassoing the times and riding them, but he found their beating hearts. Anyone could have shot Jean Babilée defying gravity onstage. William Klein filmed him eating breakfast.

***

Scout Tafoya is a writer, filmmaker, and video essayist, creator of RogerEbert.com’s long-running series The Unloved. His movies include Beata Virgo Viscera, Eyam, and House of Little Deaths, and his book on the films of director Tobe Hooper is due to be released by Miniver Press in 2021.

Stills courtesy of the Criterion Collection, William Klein's Muhammad Ali: The Greatest (1969), The Model Couple (1977) and Babilee 91 (1992).