Specialised Technique (2018) is the concluding short of Onyeka Igwe’s video trilogy No Dance, No Palaver, which also includes Her Name in My Mouth (2017) and Sitting on a Man (2018). Each film within the trilogy relates to the 1929 Aba Women’s War in Eastern Nigeria, where the Aba women protested British taxation for two years straight through the tactic of “sitting on a man”, an act of public shaming through dance that calls attention to injustice. This involves performing dances and songs that dramatise grievances against a specific figure, inhibiting him from conducting his daily affairs. The Women’s War was fomented by the colonial government’s misunderstanding of women’s power in Igbo society, resulting in what the British government called a riot. Yet, at the heart of the problem was the colonial imposition of Victorian gender ideas, which pushed a form of patriarchy onto a social system that had a more complicated relation to the entanglements of gender and power. [1]

The trilogy’s title, “no palaver”, suggests that without dancing, conflict resolution will not be permitted. Here, the director signposts to her audience that a focal shift is needed to interpret and encounter her filmic work: one that holds onto the bodily integrity of the individuals onscreen, including her own. Igwe’s trilogy is a critical tool for examining alternative modes of resistance needed by Black individuals in the UK (and globally) as they continue to face a government that is rewriting its history of colonial violence. [2] In this sense, No Dance, No Palaver is emblematic of Afro-Jamaican philosopher Sylvia Wynter's idea— found in her 1992 essay on film criticism, “Re-thinking ‘Aesthetics’: Notes Towards a Deciphering Practice”—that aesthetics, and not representation, are the visual onerous of power. [3] Igwe directs audiences’ attention towards how colonial aesthetics have written the Black body into moving image history through a global structure of anti-Blackness. I read Specialised Technique specifically for how Igwe reanimates (and remixes) resistance of the Aba women from the fixed colonial gaze of the original archive footage, restoring the embodiment that had previously been stifled.

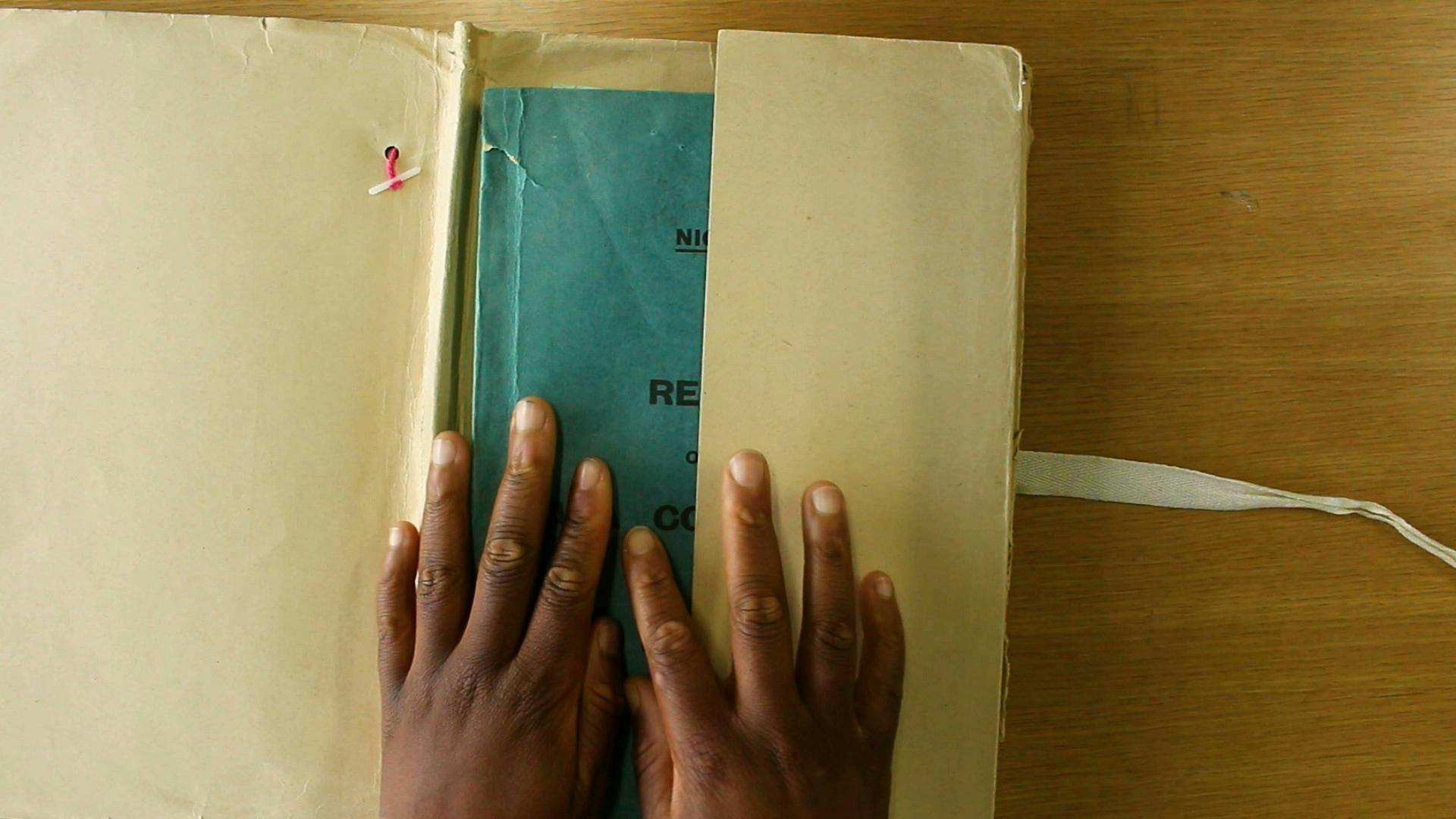

No Dance, No Palaver works through Igwe’s experience with the British Archives on Nigerian culture. The primary footage of Specialised Technique (as with the larger trilogy too) is taken from archival film of the Igbo women in Nigeria produced by British colonial officer William Sellers in the 1930s that Igwe acquired from the BFI National Archive, the British Empire and Commonwealth Museum Collection, and British Pathé. [4] In Her Name in My Mouth (2018) we see Igwe’s hands in these archives, digging through the stately packaged official history of the Igbo women as produced by the British Empire.

It is Specialised Technique that most thoroughly calls attention to the apparatuses of the camera and how to “shoot” a body in its aesthetics. Igwe works through the official discourse on shooting ethnographic footage that appears in the framing of the Nigerian women as shot by William Sellers. From what to focus on, to what to ignore, Seller’s camera “techniques” brutally defined the movement of Nigerian bodies to the world on-screen. [5] What Igwe seeks to recuperate in this archival remix, then, is a method of restoring embodiment and lived experience—by foregrounding the body’s power to act—that shows the lives within these archives. The body’s power to act, via Baruch Spinoza, refers to how bodily movements, from dancing to crying, carry power to affect others no matter how big or small.

Igwe’s artistic practice centres the ownership of archives and what we inherit from them in the present. In my interview with the artist, Igwe foregrounded two archives that were instrumental in the development of her filmic technique. The first lies with her family archive, which she started to examine following the death of her grandmother in 2014—feeling a need to rediscover this woman’s life, her Nigerian origins, and how Igwe might find herself in that narrative. Archives for Igwe, then, became a critical way for her to collapse the gulf between the ‘historical’ and her personal archive of what is missing in that space. In pursuit of this practice, Igwe volunteered at the June Givanni Pan African Cinema Archive, a critical archive of Black diasporic filmmaking made available in London by film scholar, archivist, critic, and curator June Givanni. [6] Igwe also has received her Master’s Degree in Visual Anthropology from Goldsmiths College and recently was a PhD researcher at the University of the Arts London. Through this intense archival research and practice, Igwe became interested in using experimental aesthetics to capture and shed light on the contradictions that emerge in the archives housed in colonial spaces. Many archives on racialised life are troubling and exist in troubling spaces, and thus, a radical affective response is needed to do the research and work with these images. This can pull out a similar radical affective response to these bodies that moves beyond injury and toward emancipation.

In writing about her research and artistic praxis, Igwe describes her aesthetics as attempting to shake the stereotypes out of the images: “I tried in as many ways as possible to change how the audience saw various people on camera. Converting the film to individual frames and then reanimating them, or digitally drawing on them, slowing them down or tripling them and re-projecting, were all techniques utilised in order to create a pensive spectator.” [7] What Igwe demonstrates here is how aesthetics, as produced by camera and filmic techniques, frame the body. Through the colonial aesthetics marshalled by Sellers, a Euro-American ‘eye’ received technical training on how to captivate ‘captive’ lives onscreen. By returning to the archives of the origin of technique, Igwe presents an alternative approach to this way of seeing that immerses audiences. Her approach reorients the perspective from the ocularfocus gaze of fixating and observing these women to one that restores animacy to their movements, drawing out cinema’s innate ability to generate affect.

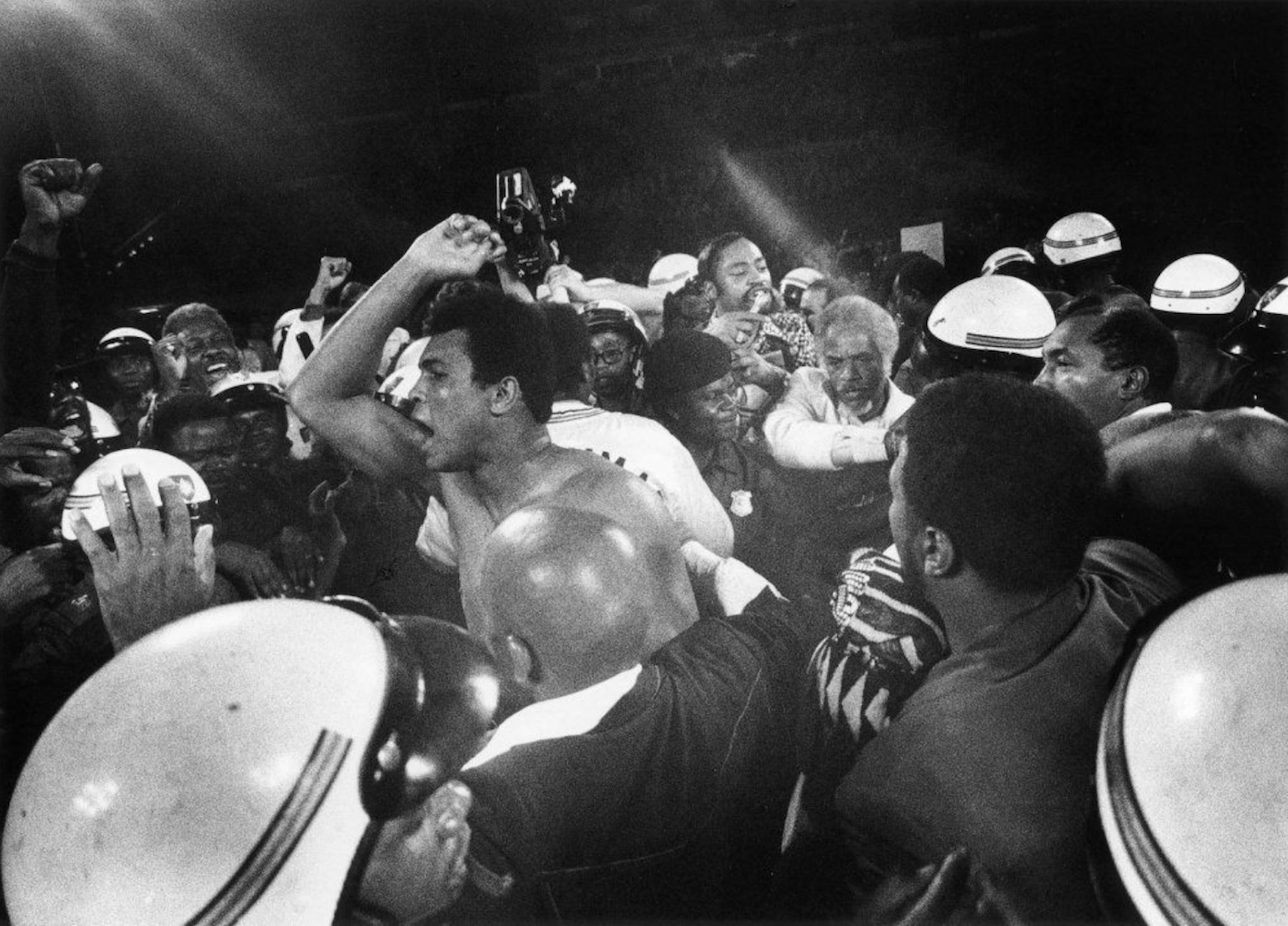

Specialised Technique opens with a woman steadfastly dancing with deep movements in her bent arms and legs. Igwe then uses animated stick figures to mirror the intensity and formal patterns of the gestures the woman completes to draw out its force as an otherness to the film itself: an opposition to the act of colonial recording that produced the original footage. We then move to a series of clips that are presumably taken from the same batch of footage on the Aba women. What Igwe does to intervene on this archive is provide a series of questions that call our attention to the frame. These include: “Do you want your whole body in the shot?,” “What happened when you looked down the lens?,” “Do you not want me to see your face?,” and “What do I want to focus on?”, to name a few. This questioning continues throughout the short, set to Seller’s archival footage of a dancing Igbo tribe. Four minutes into the six-minute short, Igwe then appears onscreen, disrupting the pattern by standing in between the beam of the projector light and the image.

Igwe literally mediates the archival images through the presence of her body: her hips as a screen. We then begin to shift our engagement from what is happening to what the film/video is doing, and more critically, what the on-screen bodies are doing, here. Igwe’s aesthetics bring to mind Sylvia Wynter’s call for experimental aesthetics to show us the illocutionary acts of cinema. [8] In “Re-thinking ‘Aesthetics’,” Wynter attends to how aesthetics, not representation, frame our perception of Blackness on a biological and social level. [9] Aesthetics shape our affective engagement of reality in equal measure to our cognitive awareness of it.

Sellers recognised this power in film when he was tasked with using cinema as an educational tool to train Nigerians during his colonial intrusion in Nigeria. [10] Sellers was a colonial British officer of sanitation, working in Nigeria from the 1930s to the 1940s. He was tasked with creating a mobile cinema, screening 16mm films on sheets in open fields to “educate” Nigerians on health and hygiene. His shorts were successful enough to develop the Colonial Film Unit (CFU), where he developed a number of observational and educational shorts for Nigerians. Sellers’ cinema techniques disavowed speciality “tricks” like whip-pan, flashbacks, reverse speed, stop motion, etc., for he felt that Nigerians would be confused by the sophistication of these filmic techniques. [11] Ultimately, Sellers’ styles had an impact in shaping the style of images coming out of Nigeria and on Nigerian people. In some ways, Sellers’ limited “observational” gaze shaped how other filmmakers approached African and Afrodiasporic bodies on film in the UK, a vision that is informed by anti-Blackness. [12]

Sellers’ cinema techniques shaped the direction of the CFU through the 1950s and held an onerous power over Nigerian filmmaking for years after. As Wynter describes, aesthetics biocentrically write out behavioural response of culture in reality. Biocentrically—which is Wynter’s neologism, and what I believe to be one of her most profound contributions to film and arts criticism—refers to the way in which we corporeally respond to images: how aesthetics determine our kin relations in society. It is a framework which enables us to see how Sellers could, in his images, collapse both the Igbo women and their cultural production. Using what Michel Foucault describes as the imperialistic eye of medicine and study, he adopts a clinical gaze on people such that it aesthetically fixates them into sequences of repetition of movement and performance for his camera. [13] This is what Fanon writes in Black Skin, White Masks as seeing colonial images of himself as a petrification of his body akin to photochemical fixer that solidifies an image in place. For Fanon, the colonial gaze is both the oppressor and liberator for it takes racialized subjects out of the world—that is removes us from kin relations with others— through image-making but also possesses the power to restore our place in the world, what Fanon describes as “[our] lightness of being.” [14]

Through the aesthetic manipulations in Specialised Technique, Igwe subverts Sellers’ style. By applying repeated or reversed frames, making marks atop the imagery, or by using stop-motion animation, Igwe uses aesthetic interventions to challenge Sellers’ “techniques”, diverting our attention to the bodies such that they are not static observational studies but affective lives with the power to act and compel us to feel. Igwe’s evocative disruption to Sellers’ intent comes through the very system that enabled his gaze: the institution and its archives. As a Black Briton of Nigerian descent, entering the British Pathé archives situates her presence as a “marked woman.” [15] Acutely aware of this mark, Igwe describes how she draws out her embodiment to honour those passages that she describes as “blood memories” of colonial collision of the UK in West Africa as “being close to, with or amongst.” [16] Paying attention to her embodiment in the archives is not only a disruption to how the archive comes to know itself as a pristine place of order, but also something that provides her with the toolkit to make kin with the women of the past. In doing so, she can bring their embodiment to the fore of the images.

Specialised Technique and the larger trilogy of No Dance, No Palaver give evidence to the way in which performance ignites affective assemblages. Elena del Rio writes about the critical, ontological properties of performance as affection onscreen; we might want to recognise the same attributes at play in Igwe’s work. Her experimental aesthetics “accommodate certain moments of pure kinetic and gestural situations where movements and gesture are given in and for themselves […] thus unfold[ing] as a series of random piercings of the narrative fabric.” [17] Igwe’s aesthetic experimentation with archival footage enables her to go against the totalising structure of fixation that lies in Seller’s original material, instead foregrounding the performances onscreen and their ability to move us and restore life into the bodies.

I consider Igwe’s approach to the cinema’s archives as an emancipatory release of Euro-American aesthetics of anti-Blackness through a more corporeal-focused engagement through her body and the lives that are housed in the British Pathé and made available for ‘study.’ This approach operates not unlike a remix, where Igwe scrambles the colonial routes and rites of passages that constitute its archival holdings and field of vision. Specialised Technique demonstrates that not only are interventions possible to the past that restore movement to those subjects, but that the past is not a petrified concept and rather one in which many avenues of approach are available. The archives (as they are represented to us) are not the only way, but rather a constructed reality made possible by a system of power. Igwe’s archival remix works expansively and experimentally across footage to aesthetically release Black women’s bodies in time.

***

Ayanna Dozier is an artist, lecturer, curator, and scholar. Her dissertation, Mnemonic Aberrations, examines the formal and narrative aesthetics in Black feminist experimental short films in the United Kingdom and the United States from 1968-present. She the author of the 33 1/3 book on Janet Jackson’s The Velvet Rope from Bloomsbury Academic Press. Her artistic practice is located in film (both still and Super 8 and 16mm motion picture) and performance, paying close attention to experimentation in those mediums. She is currently a Joan Tisch Teaching Fellow at the Whiney Museum of American Art, a lecturer in the Department of Communication and Media Studies at Fordham University, and was a 2018-2019 Helena Rubinstein Critical Studies Fellow in the Whitney Independent Studies Program. She resides in Brooklyn, NY. https://dozierayanna.com/

Republished from Issue 02: Network of Open City Documentary Film Festival’s Non-Fiction Journal. You may order a printed copy here. Stills courtesy of the artist and LUX.

***

[1] Andrew Hibbard, “Okwui Okpokwasili and What it Means to Sit on a Man” Frieze June 3rd, 2019, https://www.frieze.com/article/okwui-okpokwasili-and-what-it-means-sit-man.

[2] These are forms of violence that are still felt by Black Britons as they combat injustice against the Windrush generation, police brutality, discrimination and the limitations of travel, low wages, and rampant housing inequality.

[3] Sylvia Wynter, “Re-thinking ‘Aesthetics’: Notes Towards a Deciphering Practice” in Ex-iles: Essays on Caribbean Cinema, eds. Mbye B. Cham (New Jersey: Africa World Press, Inc., 1992), 239.

[4] Onyeka Igwe, “Being Close to, With or Amongst” Feminist Review no. 125(2020): 44-53.

[5] Brian Larkin, Signal and Noise: Media, Infrastructure, and Urban Culture in Nigeria (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008).

[6] Interview with the artist in 2018.

[7] Igwe, “Being Close to, With or Amongst” 51.

[8] Wynter, “Re-thinking ‘Aesthetics’,” 267.

[9] Ibid, 254.

[10] It is perhaps important to note that what most would now consider an ‘intrusion’ is still defined as a ‘stay’ by many institutions.

[11] Larkin, Signal and Noise, 108-109.

[12] Anti-Blackness here refers to global material and immaterial acts forged through the transatlantic slave trade that ontologically positions all fields of thought and production on the belief that Black people exist outside of the field of the human. Sylvia Wynter, “No Humans Involved: A Letter to My Colleagues,” Forum N.H.I.: Knowledge for the 21st Century no. 1, 1(1994): 1-17.

[13] Michel Foucault, The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception translated by Alan Sheridan (New York: Vintage Books, [1973] 1994).

[14] Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks translated by Richard Philcox (New York: Grove Press, 2008), 89.

[15] Hortense Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book,” Diacritics no. 17, 2(1987): 65.

[16] Igwe, “Being Close to, With or Amongst” 47.

[17] Elena del Rio, Deleuze and the Cinemas of Performance: Powers of Affection (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2008), 29.