“What’s it matter if the truth is that their favoring breeze has the stink of nickel whiskey on its breath, and their sea is a growler of lager and ale, and their ships are long since looted and scuttled and sunk on the bottom? To hell with the truth! … The lie of a pipe dream is what gives life to the whole misbegotten mad lot of us, drunk or sober.”

So sermonizes Larry Slade, the most clear-eyed denizen of Harry Hope’s Saloon in Eugene O’Neill’s besotted stage epic The Iceman Cometh. A fatalistic philosopher with no audience but the self-deluded barflies who call the Greenwich dive their home, Larry deems the place “Bedrock Bar, the End of the Line Café … the last harbor. No one here has to worry about where they’re going next, because there is no farther they can go.” The dive bar is a stock locale in popular culture, ubiquitous in the pages of Charles Bukowski, the lyrics of Tom Waits, and films like Steve Buscemi’s Trees Lounge (1996). It turns up in nonfiction film too, on occasion, and always in ways that reveal the porous nature of the form. What we’re shown is never entirely free of artifice, which seems only right for sodden hideaways whose stale air is thick with fabulism, and whose frequenters, as eager to impress as they are to escape reality, “would rather go without food and water than tell you the truth.”

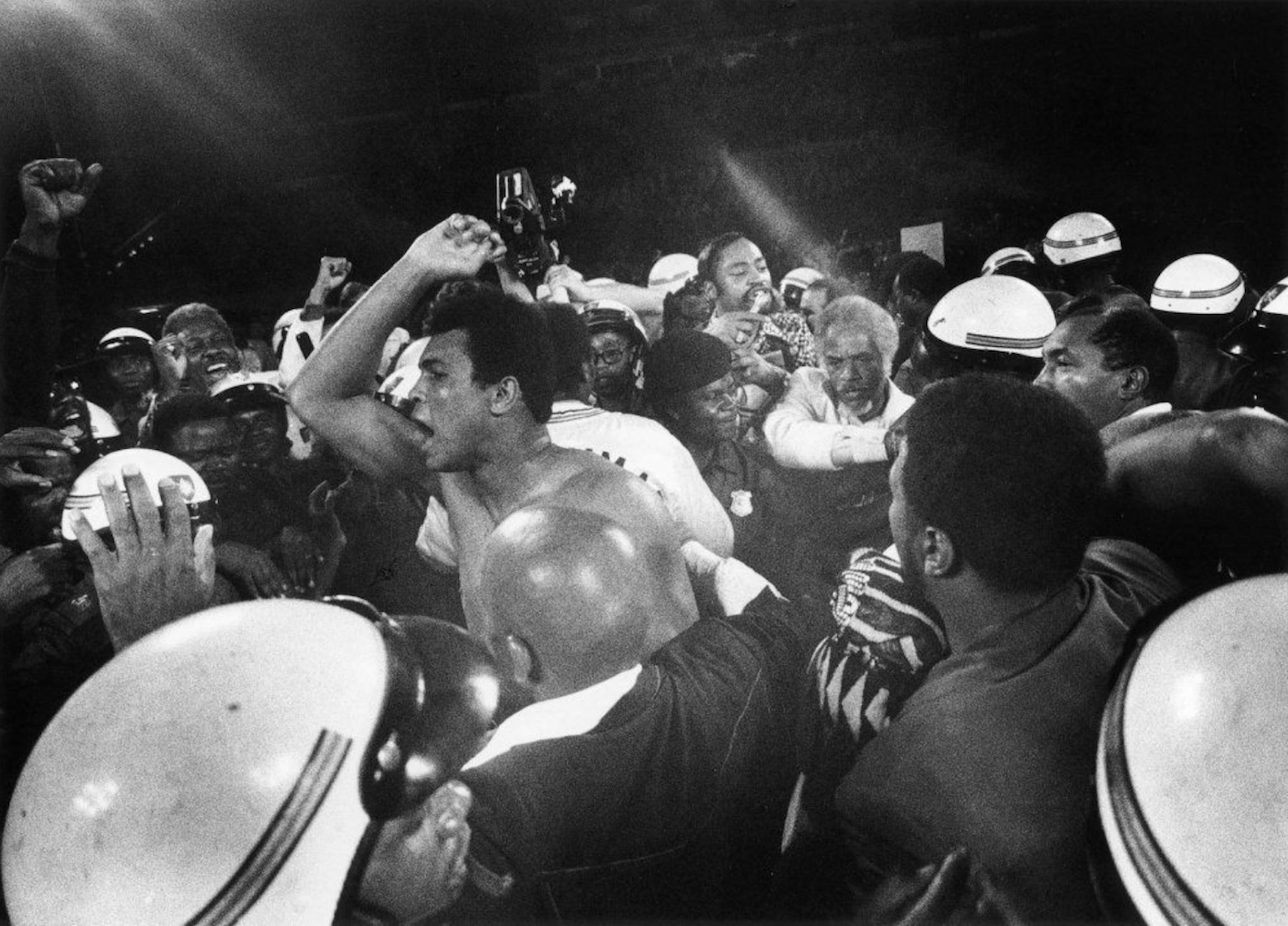

That observation issues from Cowboy, the would-be Gary Cooper clone at the center of Eagle Pennell’s landmark independent feature Last Night at the Alamo (1983). Though it’s scripted by The Texas Chain Saw Massacre’s Kim Henkel and cast with professional actors (“Cowboy” is played by Sonny Carl Davis, whose seven dozen credits include Bernie by Pennell acolyte Richard Linklater), to watch the film is to undergo a sort of hypnosis. The setting (the titular locals’ bar on the eve of its demolition) feels so real, the aesthetic so grab-and-go unvarnished, the line of bull so familiar to the ear of anyone who’s passed blurry hours at watering holes like this one, that learning of the film’s production—it was shot over three and a half weeks in the Old Barn, a real East Houston tavern that required the crew to wrap by 4pm each day so it could open for business—only adds to its authenticity. It never purports to be a documentary, but despite its dramatic architecture, it strives to capture with sincerity what is unique and endemic to these peculiar spaces.

The great appeal of dive bars (as opposed to cocktail bars) is that within their walls patrons can be italicized versions of themselves: more irascible, more sentimental, or simply more. As patrons grow into regulars, familial bonds develop, along with an unspoken compact that every day is a reset with past aberrant behavior disregarded (or literally forgotten). The blatant theatricality engendered by the laxness and comfort of the surroundings may suddenly turn on itself, with gregarious barflies retreating inward as night falls on their day drinking. These moments are difficult to stage in film because they are just moments—unheralded, unpredictable. Yet a passive spectator or fly-on-the-wall filmmaker might likewise miss out, their vow of non-interference costing them precious on-camera discoveries. Thus, effective nonfiction studies of bars must be cocktails of a sort—one part manufactured scenario, two parts observation, shaken and served with a twist.

Pennell, whose own alcoholism cut short a promising career and cost him his life at 49, knew his milieu all too well. The much-admired Cowboy’s fall from grace—a failed seduction leads to a humiliating scuffle in the parking lot, and later rejection by the woman who tends his wounds—feels less like a narrative arc than a nightly ritual. Were there to be a next night at the Alamo, the bald-pated, anachronistic braggart would still be everyone’s hero, because he talks a better show than anyone else, and one day he swears he’ll be in the movies (“the lie of a pipe dream”). Swirling around him are streams of self-pity from his comrades-in-booze, by turns vernacular (“He’s wound up tighter’n a two-dollar wristwatch”) and profane, always circling back to the same anxieties: irrelevance, emasculation, and changing societal norms. Cowboy decries the encroachment of fast-food restaurants and condominiums; the replacement of John Wayne with Robert Redford and John Travolta; and the fact that even if the Alamo bar is saved, it won’t be Walter Cronkite covering the rescue effort on the nightly news but some younger heir. As Pennell understood, the truth on display derives not from whether an oil-rig worker known as Cowboy ever stood in a crumbling pub called the Alamo and held forth on the dire appearance of “Yankee bars” with tacky mechanical bulls, but from the fact that you can walk into any such pub in any part of the country and hear drunken, angst-ridden men projecting their diminished self-worth onto cultural phenomena that they fail to comprehend.

The prototype of this hybrid genre of bar films is likely to be Lionel Rogosin’s 1956 skid row exposé, On the Bowery. Called “[i]n a very real sense the ultimate New York movie” by a Village Voice reappraisal in 2010, Rogosin’s film attempted to wrest the blame for alcoholism away from the moral failings of the individual. As the director claimed, he and his collaborators viewed “the alienation generally at work in American society” as the culprit, blaming a callous capitalist system for perpetuating “loneliness, ignorance, and futility.” Uncredited screenwriter Mark Sufrin told Sight and Sound that the film’s “actors were taken from the street and would speak in their own argot, with guides of what to say only for story purposes. Direction on our part would try to define the action, but not gesture or inflection.”

In viewing On the Bowery—which was nominated for a Best Documentary Feature Oscar—over six decades after its release, the guiding hands of Rogosin and Sufrin are visible in how loose interactions are sculpted into a story in which railroad worker and former GI Ray Salyer befriends older ex-newspaperman Gorman Hendricks. Both are alcoholic vagrants, and though Hendricks steals Salyer’s suitcase while the younger man is passed out, he ultimately pays him back, hoping that Salyer will leave the Bowery and begin anew. Despite Sufrin’s claims, some less than naturalistic dialogue (“Probably some of your drinking companions hauled you in there by your pockets”), overly decorous performances (which led to the the craggily handsome Salyer being offered a $40,000 Hollywood contract that he turned down), and Charles Mills’s Chaplinesque score lend the film an unmistakable docufiction vibe common to nominal docs of the period. On the other hand, sequences of indigents asleep in seedy barrooms or crowded into a Bowery mission—forced to listen to a patronizing sermon before they are fed, and told they will have to stay sober and fumigate their clothes if they want a place to sleep—paint a more vivid picture. Many of them choose saloons or makeshift shelters of upturned pushcarts over the constant scrutiny of sanctimonious guardians. Cinematographer Richard Bagley (himself an alcoholic who died five years later at 41) captured these incidents with a 35mm camera hidden in a bundle or in the back seat of a car. Private moments writ large for public empathy.

The aims and techniques that animate Alamo and Bowery are consolidated in this year’s Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets, co-directed by Bill and Turner Ross. Another valedictory to a beloved local hangout—the reassuringly dingy “Roaring 20s” bar in Las Vegas—on the day before its closure, Bloody Nose is something mellower and less despairing than its stark, black-and-white predecessors: an ode to voluntary families, despite the eloquent insistence of Michael, a failed actor and the establishment’s elder statesman, that the people you hang out with in a bar are not your kin. Each new arrival is greeted like Norm on Cheers, with the bartenders (a dry-witted guitar player with a ZZ Top beard in the daytime and a no-nonsense single mom at night) keeping discourtesy at bay and unobtrusively picking up cab fare for sedated regulars. The cinematography by the Ross brothers is warm and glistening, attuned to the browns of wood-paneled walls strewn with holiday lights, giving off an indistinct glow that simulates the effects of a long, woozy day spent in one spot.

The customers’ tearful farewells could only spring, it would seem, from long-standing friendships brought to a hasty, unsought end. But in point of fact the Roaring 20s bar is located in New Orleans, the city where the filmmakers shot their 2012 documentary Tchoupitoulas, and which they now call home. The habitués are all actors—some professional, like Michael Martin (who’s still working, unlike his onscreen counterpart), and others selected by the Ross brothers out of personal acquaintance or instinct. Local news and traffic reports are shoehorned in, while the Vegas exteriors (overlaid by filters turning the air the color of Mountain Dew, inducing an urgent desire to retreat indoors) were shot in some cases a decade earlier. But whatever liberties were taken with the cast, the drinks poured into them and the improvisatory feelings poured out of them are devoid of fabrication.

The gradual erosion of clarity is an essential component of the dive bar experience, too often neglected in fictional accounts. (Ever notice how Norm and Cliff are just as witty at Cheers’s last call as when they ambled in 17 hours prior?) But Bloody Nose is minutely cognizant of this reality: Michael, who is so chipper in the morning, hanging party favors on the walls and waxing theoretical, is by nightfall semi-conscious on a couch, barely able to croak out a warning to a younger patron not to throw away his future to hold court in a bar. His is the poignant, rueful voice of experience. Bill Ross’s editing reinforces the sense that taverns are Bermuda Triangles for time: as the numerals of a digital clock periodically flash onscreen, the three-hour lapses make viewers wonder how long they’ve been sitting there, watching these people banter and drink.

It seems hardly relevant that the figures in the bar have in actuality only known each other a short while; the space is real, the booze is real, the debates spurred by drink (sometimes political, frequently profound) are real, and in the end, the tears are real—particularly those of Bruce, a veteran whom the Rosses found in a bar at 2am and chose for his emotional transparency. At one point, Michael, discussing his stint as an actor, recalls that he used to seek the truth of every scene; upon discovering he could never find it entirely, he shifted his focus to the pursuit of beauty, “what pleases the eye.” This he soon recalibrates to “what pleases the spine, you know what I mean? When something goes up the back of your spine.” Emotional truth, in other words. It’s what the Rosses are after, and what Pennell and Rogosin were after, too. And it gives life to the whole misbegotten mad lot of us, drunk or sober.

***

Steven Mears is the copy editor for Field Notes and for Film Comment magazine, as well as a frequent contributor to Film Comment’s print and web editions, Metrograph’s Journal, and other publications. He received his MA in film from Columbia University, where he wrote a thesis on depictions of old age in American cinema.

Stills courtesy of The Ross Brothers, On The Bowery (1956) and Last Night at the Alamo (1983).