There is an irony to the fact that the most well-known film by the American director William Greaves (1926-2014) also happens to be his most atypically out-there, experimental piece of work. In the unclassifiable Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One (1968), we see Greaves filming a movie scene in Central Park that depicts a repetitive argument between a couple. Simultaneously, a documentary crew films the crew filming the fictional movie. Meanwhile, a third crew documents the filming of the two films. Throughout, Greaves, sporting a natty green mesh T-shirt, convincingly plays the role of an aloof, clueless artist, while on-set conditions deteriorate and nerves start to fray. His increasingly furious (and mostly white) collaborators, feeling abandoned, begin to mutiny.

How much of all this is “real”? How much is “staged”? Does it matter? Concrete resolutions are jettisoned in favor of purposefully provocative ambiguity, and the end result is a discomfiting study of intersecting racial and power dynamics within the context of low-budget filmmaking. As critic Michael Koresky has observed, “although it is never spoken about in the film, the fact that Symbiopsychotaxiplasm was made by an African-American man in the 1960s cannot be ignored: Greaves’s race is unavoidable and ever-present.”

Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One becomes even more compelling when one considers what else was happening in Greaves’s professional life around the time the film was made. Greaves, who had trained as a filmmaker at the National Board of Canada owing to a paucity of opportunities for Black filmmakers on home turf, returned to America to cover the civil rights movement. In August 1968, months after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., and the sustained rioting that followed, Greaves was appointed executive producer of the landmark public affairs program Black Journal, the first nationally televised, regularly scheduled show of its type to focus on African-American life. Black Journal was publicly funded in response to the Kerner Commission report into the previous year’s civil unrest (or, as Black Journal contributor Madeline Anderson once put it to me in an interview: “They decided, ‘Hey, maybe one of the ways of controlling them is to give them some programming. Let them look at TV and maybe they won’t go out and burn down things.’”)

Greaves was only promoted from co-host to executive producer when his Black colleagues insisted that the incumbent, a white man, was unsuited for the job, and went on strike. A year later, Greaves won an Emmy for his work on the program. To me, viewed in this context, Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One—and Greaves’s borderline baroque performance of ineptitude within—has always read as a particularly acidic parody: a projection of the worst fears that white creatives have about handing over control to those whom, deep down, they consider to be inferior.

After languishing in obscurity for decades, Symbiopsychotaxiplasm was released theatrically for the first time in 2005 and on DVD the following year, alongside a newly filmed sequel (Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take 2 1⁄2). Retroactively subtitled Take One, the original has attained a cult following of late among art-house film fans and a new generation of contemporary nonfiction practitioners who take cues from its exploration of formal hybridity, and its complication of conventional notions of documentary “objectivity.”

Yet Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One and Greaves’s contributions to Black Journal are only two pieces of the vast jigsaw puzzle that is the filmmaker’s body of work. According to a filmography assembled by the scholar Aurore Spiers for Scott McDonald and Jacqueline Najuma Stewart’s forthcoming book William Greaves: Filmmaking as Mission, Greaves was director, producer, writer, cinematographer, and/or editor on no less than 79 films in a period spanning 1953-2005. (Prior to 1953, the Harlem-born Greaves enjoyed stints as a recording artist and an actor.) These credits are listed on williamgreaves.com, a new website created and launched this year by documentary filmmaker Su Friedrich alongside Louise Greaves, William’s collaborator and spouse of 55 years. Rich in biographical detail, the site offers an invaluable window onto the life and work of a pioneering artist who deserves to be known and appreciated far more broadly.

The launch of the website coincides with the emergence this year of another key piece of the Greaves puzzle: the full-length, 80-minute version of his 1972 documentary Nationtime, hitherto only circulated in a 58-minute cut intended for television, and previously known as Nationtime—Gary. It’s something of a miracle that we’re able to see it at all: in 2018, Carnegie Mellon archivist Emily Davis identified the film’s 10 original color reversal A&B rolls among 70,000 picture and sound elements in a Pittsburgh warehouse. The film was subsequently restored by conservation company IndieCollect, and distributed in North America by Kino Lorber.

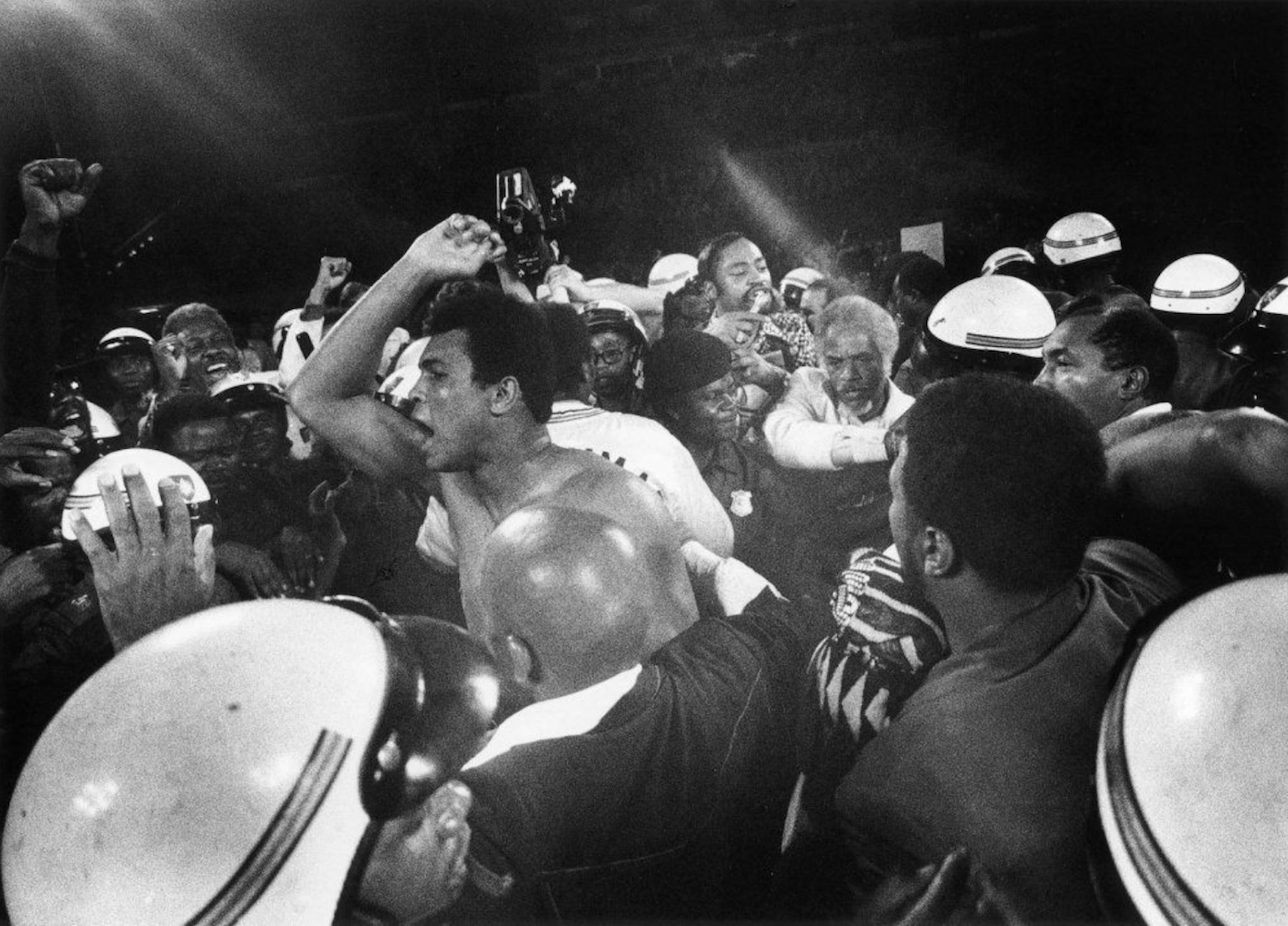

Financed, produced, directed, and chiefly shot and edited by Greaves himself, Nationtime is a pulsating record of the National Black Political Convention that took place in Gary, Indiana in March 1972. As observed by scholar Leonard N. Moore, a key aim of this three-day event was to end the intense feud that had effectively divided black activists into two broadly defined camps—integrationists and Black nationalists—in the four years following King’s assassination. The NBPC brought together around 8,000 people, including 4,327 official delegates, Black elected officials from multiple states, veterans of the civil rights movement, and Black Power advocates. They sought to find consensus on a political strategy that would mobilize Black political power at all levels nationwide, and guide them through the looming 1972 election season.

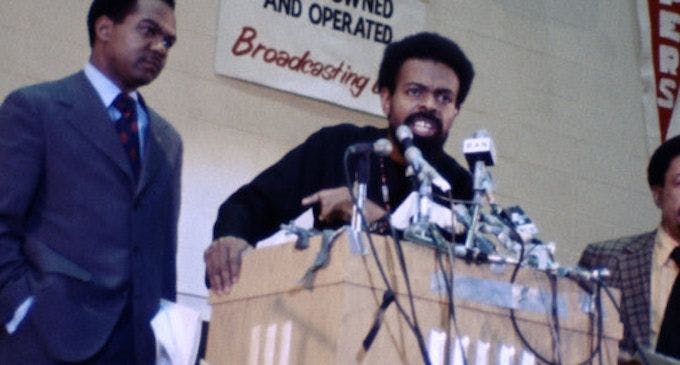

Despite a minimal budget and myriad lighting and audio challenges, Greaves and his small crew—including his son David on second camera and brother Donald on sound—captured the excitement and vast emotional vacillations of the conference with sensitivity and a keen sense of detail. Thronging crowd scenes within the conference hall are punctuated by heart-stopping close-ups of attendees and participants, revealing every emotion from joy to hope to anxiety. There are rousing speeches by the Reverend Jesse Jackson, Amiri Baraka, Betty Shabazz, Bobby Seale, comedian Dick Gregory, and Gary’s mayor Richard Hatcher, whose fiery opening remarks are freighted with sentiments that feel especially resonant in 2020. “The 1968 National Party Conventions made a mockery of the democratic process,” he rails. “They were drunken carnivals run for the exclusive few … they debauched the electoral process, and shattered the idealistic hopes of youth … [we must] liberate America from its current decadence!” Outside the conference hall, attendees mingle and give interviews to the press. Legendary civil rights activist Queen Mother Moore passes out leaflets and loudly calls for the introduction of reparations for slavery—a subject that continues to be debated today, especially after Ta-Nehisi Coates’ watershed 2014 essay “The Case For Reparations” brought it back to the forefront of the political conscious. It’s just another moment in this 48-year-old film that feels strikingly contemporary. Drawing upon years of experience in making punchy content for public television, Greaves cuts it all together with an expert flow.

Nationtime’s first half is one big upswing, culminating in Jackson’s long, electrifying speech, which features the call-and-response chant from which the film takes its title (“What time is it?” “Nation Time!”) The wheels come off somewhat in the second half, which begins with Baraka—one of the originators of the conference—imploring attendees to behave themselves because the eyes of the world are upon them, and press reports from the first day had not been positive. Disaster strikes when a large section of the Michigan delegation exits the conference in high dudgeon, while an increasingly frazzled-looking Baraka pleads for unity and calm. The close-ups of Baraka’s pain-etched face offer a window on the sheer weight of responsibility on his shoulders and lend the film considerable emotional weight.

Greaves neither shies away from depicting nor attempts to smooth over the tensions of the conference. Instead, in an editorial masterstroke of great poignancy, he intersperses throughout the film a dual set of voiceovers: a Greaves-penned narration voiced with grand dignity by Sidney Poitier (“Out of the long winter night of our oppression in America we are witnessing the birth of a new golden age for our people”); and poetry by Langston Hughes and Amiri Baraka read by Harry Belafonte. Both speakers are recorded to sound as echoey and stentorian—if not positively godlike—as possible, adding a celestial dimension to this bustling, boots-on-the-ground documentary. The voiceovers, taken in tandem with the exhilarating onstage musical performances by the likes of Isaac Hayes, render political expression indivisible from artistic creativity, and contribute to the film’s hypnotic power.

William Greaves’s passion for his work on Nationtime is encapsulated by a beautiful anecdote told by his son David in the pages of Filmmaking as Mission:

“[After Jesse Jackson’s speech] the music was up, and everybody was dancing. In my camera I could see my father panning, focusing, zooming, but later I could not find those shots anywhere in the footage … When we were viewing the footage and came to the overhead shot where we see him shooting, I told Dad I’d looked at every roll of film we had but couldn’t find that one. Dad said I wouldn’t find it: ‘There was no film in the camera.’ ‘Then what were you doing?’ He responded wistfully, ‘It was such a great shot, I didn’t want to miss it.’”

In this moment, as in Symbiopsychotaxism, Greaves was “playing” the role of a filmmaker. Here, though, there was no irony, no provocation. Just a man on a mission blissfully lost inside a moment. Now, thankfully, that moment is ours to share.

***

“Nationtime”is available to stream in virtual cinemas nationwide and“Symbiopsychotaxism: Take One”and“Take 2 1⁄2” are out on Blu-ray this month via the Criterion Collection.

***

Ashley Clark is the curatorial director at the Criterion Collection. Previously, he worked as director of film programming at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, and he has curated film series at BFI Southbank, the Museum of Modern Art, TIFF Bell Lightbox, and the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture, among other venues. He has contributed writing to publications including Film Comment, Reverse Shot, Sight & Sound, and the Guardian. His first book is Facing Blackness: Media and Minstrelsy in Spike Lee’s “Bamboozled” (2015).

Stills courtesy of Janus Films and Kino Lorber / Indie Collect.