Some of the last films I saw in repertory cinemas before all of New York’s movie theaters shut down in March 2020 were video works from the height of the AIDS epidemic. In early February, Carson Parish at the Museum of Modern Art curated a series called “Now We Think as We Fuck: Queer Liberation to Activism.” The title comes from the poet Essex Hemphill, who recites it to the camera near the end of Marlon Riggs’s 1989 filmic essay on Black homosexuality, Tongues Untied: “Now we think as we fuck / this nut might kill / this kiss could turn to stone.”

In addition to including several milestones of queer cinema, such as Shirley Clarke’s Portrait of Jason (1967) and Cheryl Dunye’s The Watermelon Woman (1996), the MoMA series also served as a good introduction to the prolific genre of AIDS video activism. Titles such as Gregg Bordowitz’s Fast Trip, Long Drop (1993), Jean Carlomusto and Maria Maggenti’s Doctors, Liars, and Women: AIDS Activists Say No to Cosmo (1988), and Gay Men’s Health Crisis, Inc.’s Chance of a Lifetime (1985) were digitally preserved from their original U-matic and Beta SP tapes by MoMA and held in the museum’s collections.

At the time of the screenings, visual art by HIV-positive artists working at the height of the AIDS epidemic was a topic heavy on my mind. I had just finished editing a project that involved archival material from an AIDS-oriented group exhibition organized by photographer Nan Goldin at New York City’s Artists Space gallery at the end of 1989, called Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing. The title of the show produced a sort of semantic panic within me. There is no word more terrifying to an archivist than “vanish,” I thought to myself, and then dwelled on this thought until it became a burgeoning, stoking prod of anxiety. “Vanish” implies an absoluteness that is unrecoverable—a disappearance that leaves no space for mourning, for memory, for any record of an existence. Witnesses—which acquired national attention even before it opened when the National Endowment for the Arts briefly withdrew their funding after deeming the works on display to be “of questionable taste”—showcased visual artists from the Lower East Side who had been personally affected by the AIDS crisis. Many were HIV-positive, and some, like Peter Hujar, had recently died of complications from the virus. All had found their social circle devastated by loss. “WE REFUSE TO ALLOW THE U.S. GOVERNMENT TO LEGISLATE OUR INVISIBILITY,” began the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power’s (ACT UP) response to the NEA’s withdrawal. “WE ARE THE PUBLIC.”

“Witness” and “invisibility,” along with “vanish,” are terms that crop up with relative frequency in artworks and oral histories from the AIDS crisis. Vanishing begets an empty space waiting to be filled in; it involves “the dynamics of death and replacement,” to invoke the title of the first chapter of The Gentrification of the Mind by AIDS historian and writer Sarah Schulman. When Schulman writes about watching from her stoop as New York’s East Village is overtaken by “toned-down flavors, made with higher quality ingredients and at significantly higher prices, usually owned by whites, usually serving whites,” she is talking about cuisine, but she might as well be talking about art. Photographer and filmmaker David Wojnarowicz and other HIV-positive artists sought refuge and space for art-making in both the Village and the cruising spots of the Chelsea Piers. Their deaths allowed room and opportunity for the “professional” art world to flood in, replacing their lofts and studios with pricey galleries that capitalized on their artistic credentials. In her book, Schulman recounts an anecdote related to her by the dancer Scott Heron about the porn theater on 14th Street and 3rd Avenue that would show AIDS activist videos on a loop in its basement, and where Wojnarowicz likely met his future life partner, Tom Rauffenbart. The building is now a CVS, and while reading Schulman’s book, I realized with a pang that I know it too well: right above that CVS is the college dormitory I lived in when I was 19.

***

The filmmakers in MoMA’s series met in affinity groups within ACT UP and began documenting actions and protests, as well as using their cameras to hold police at the events accountable. The first independent media-making group within ACT UP was Testing the Limits, a collective that formed in 1987 and included Bordowitz, a mainstay among ACT UP’s filmmakers. The group’s work is documented in archivist Jim Hubbard’s 2012 film, United in Anger: A History of ACT UP (co-produced by Schulman, who, along with Hubbard, founded ACT UP’s Oral History Project). A good portion of United in Anger focuses on ACT UP’s media savviness and their dedication to documenting and distributing their own images of the AIDS crisis, as opposed to relying on media narratives. This was made possible by the affordability and portability of video equipment, and the immediate turnaround it enabled from shooting to editing.

In the two years after Testing the Limits’s founding, more video affinity groups began to take shape within ACT UP, including DIVA TV (Damned Interfering Video Activist Television) in 1989. DIVA TV member Catherine Gund recalls in United in Anger that cameras were omnipresent within ACT UP to the point of being “an extension” of the activists themselves. These tactics in political video-making were inherited from the radical filmmaking collectives of the 1960s and ’70s—including New York’s Videofreex and the feminist group Les Insoumuses in Paris—who saw the potential for immediate public dissemination of countercultural information in the release of the Sony Portapak, the first portable tape-based video camera. Video also offered the ability to record and critique broadcast media: just as Les Insoumuses remixed media headlines to polemical effect in their 1975 film Maso et Miso vont en bateau, in lesbian filmmaker Barbara Hammer’s Snow Job: The Media Hysteria of AIDS (1986), digitally warped scans of newspapers proclaiming “IDENTIFY ALL THE CARRIERS… HOW AIDS COULD DESTROY AMERICA” attack the screen as a soundtrack of radio broadcasts lays the blame on gays and addicts.

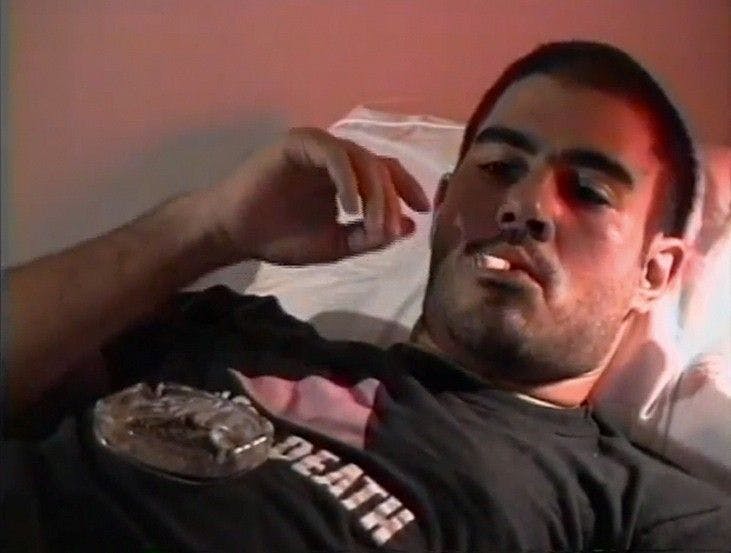

Most of the video content in “Now We Think as We Fuck,” and ACT UP’s ouevre in general, employs a first-person perspective and a sense of urgency. They bring to mind cultural critic José Esteban Muñoz’s proposition that queerness is a constant state of becoming, “a structuring and educated mode of desiring that allows us to see and feel beyond the quagmire of the present.” The videos thrum with the fury, tedium, and communal spirit of filmmakers who knew that the disease might take them at any moment. Philosopher and activist Félix Guattari wrote that Wojnarowicz created art “in order to forge himself a language and a cartography enabling him at all times to reconstruct his own existence”; the same can be said of Gregg Bordowitz and much of Testing the Limits’s work. Bordowitz’s Fast Trip, Long Drop opens with the director filming himself in his underwear as he lies on his bed and waits for his doctor to call him back with test results. “I’m just home… trying to amuse myself,” he tells the camera. The film is a seánce of the self—the autobiography of an artist who believes it will be his last work. It careens between sections of memoir, in which Bordowitz is haunted by the accidental death of his absentee father years ago and tenderly asks his mother to reflect on his coming out; venomously disaffected parodies of the media treatment of people with AIDS, featuring Bordowitz in a hellish faux–talk show where he is commanded to “represent” the HIV-positive by appearing brave and demure; and conversations with activists and friends, including the filmmaker Yvonne Rainer. By the end, Bordowitz explicitly reveals the intention behind the film: “Before I die I want to be the agent of my own history.”

Bordowitz and documentarian Jean Carlomusto brough ACT UP NYC’s video work to the AIDS education nonprofit Gay Men’s Health Crisis, Inc., which broadcast them on public television. Carlomusto became the de facto video editor for the organization. “It became sadder and sadder to sit in an editing room with this material, because as you would look at the material you’d start to think, oh, well, he’s gone, he’s gone…” Carlomusto says in United in Anger. “[ACT UP’s video work] became more and more a record of loss. In that way, the material that had once been so energizing starts to become almost a burden.” This is the impossible dichotomy of the queer video works of the era: they exemplify a moment of boundless creativity, anger, and pure collective energy, but just as immediately became archives of death and mourning. Poet Charles Theonia and writer and artist Theodore Kerr discuss this when speaking of Gregg Araki’s Totally F***ed Up (1993) in a 2016 issue of Dirty Looks zine. Kerr states that “videotape always means AIDS for me… [it’s] deployed as shorthand for doom in gay men’s lives.“ Theonia counters that their “primary association with videotape is a feeling of excitement about marginalized people getting more access to image production.” [1] These thoughts run in tandem: the videos are both memories of the deceased and instructions for a queer future.

***

Almost exactly a year after attending “Now We Think as We Fuck,” I watched the videos cited in this piece—the ones that remain unpreserved—by myself in my bedroom on a small screen. Wading through the thickets of the anonymous YouTube, Vimeo, and Dailymotion channels where they are unceremoniously uploaded in 240p, obscured by soft focus and streaking pixels, I was grateful that someone, somewhere, put in the time to make these works accessible. But it was not lost on me that the works now mirror the conditions in which their makers persevered: at risk. How easy and quick it would be for the accounts hosting them to shut down, for the videos to be deleted by an algorithmic copyright infringement bot that detects a pop song in a scene, for the work to vanish.

The practice of moving-image archiving is slow and multifaceted. It encompasses the inspection of prints, their proper care and housing, cataloguing, creating duplicates, and digitization. Typically, works in a public nonprofit archive are prioritized based on interest from researchers. AIDS video works were not made with longevity in mind, nor were they made for anything resembling financial gain. The filmmakers’ goals were immediate: a need to preserve their existence, which was under immediate threat; immediate accountability from the state; and immediate public education on safe sex. Both the creation of these works and their care and management fall under the banner of what writer and media historian Cait McKinney calls “information activism”—the often unfunded and invisible “unspectacular” labor that makes hard-to-access information available to marginalized communities.

The largest collection of AIDS video work—which includes the archives of Bordowitz as well as the prolific DIVA TV video-maker Jim Wentzy—resides at the New York Public Library. These archives were brought to the NYPL by Hubbard in the mid-’90s [2] from the basements and apartments they were languishing in until then, unduplicated from their unstable Hi8 master tapes [3]. The works in these collections are now around 30 years old, which is coincidentally the estimated lifespan of most tape formats under ideal archival conditions. After this point, the tapes are increasingly “high-risk”: hydrolysis causes the binder around the magnetic tape to develop “sticky-shed syndrome,” an ailment with no cure. At this stage the archivist must consider the prospects of “baking” the tape, or exposing it to high temperatures in order to briefly quell the rot for a last shot at digitization.

The considerable technical challenges of preserving obsolete tape formats aside, many queer archives continue to face political scrutiny for containing material that may be deemed pornographic, or subject to homophobic state legistlation. (East Tennessee’s Voices Out Loud archive, for example, was founded in direct response to Public Chapter 1066, House Bill No. 2248, which defunded the University of Tennessee, Knoxville’s Pride Center on the grounds that state funds shall not “promote the use of gender neutral pronouns.”) There are also ethical concerns. Are these videos private or public, and thus how accessible should they be? Should the archivists working with the material be queer? How will the taxonomy of the collection’s metadata age in relation to a community that is in a perpetual state of redefinition?

More queer video material is certainly out there, unidentified or unprioritized, and grassroots initiatives are attempting to preserve these works. In December 2019, the New York–based, volunteer-run digitization group XFR Collective presented videos from their residency at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art [4], where they had allowed museum members to bring in at-risk VHS, Betacam, Hi8, and U-matic tapes. The results included PSAs from Gay Men’s Health Crisis, Inc.; protest footage; and Homoteens filmmaker Joan Jubela’s 1993 appearance on New York City public-access show Dyke TV.

“What have we internalized as a consequence of the AIDS crisis?” Schulman asks in the conclusion of Gentrification of the Mind. “As with most historical traumas of abuse, the perpetrators—the state, our families, the media, private industry—have generally pretended that the murder and cultural destruction of AIDS, created by their neglect, never actually took place… They probably believe, as they are pretending, that the loss of those individuals has had no impact on our society, and that the abandonment and subsequent alienation of a people and culture does not matter.” The main risk that AIDS-era video works face is that of being classified as ephemera as opposed to pioneering, pre-gentrification nonfiction cinema. The videos in “Now We Think as We Fuck” and the New York Public Library’s collection are simultaneously playful and furious, hopeful and terrified. They collectively demonstrate a queer cinema not of assimilation or mainstream representation, but in defiance of being forgotten.

***

Mackenzie Lukenbill is an audiovisual archivist and editor from Rochester, NY. Previously, they were the data manager for Field of Vision and a consulting programmer at Newfest. They have contributed writing to BOMB Magazine and Film Comment.

Stills from Fast Trip, Long Drop (1993) image copyright of Gregg Bordowitz, courtesy of Video Data Bank at School of the Art Institute of Chicago, United in Anger: A History of ACT UP (2012) by Jim Hubbard (original shot of Keri Duran by Ellen Spiro), and Totally F***ed Up (1993).

***

[1] Theonia, Charles, and Theodore Kerr. “You Used to Call Me on My Land Line.” Dirty Looks, vol. 1, 2016, pp. 96-101.

[2] Hubbard, Jim. “AIDS Activist Video and the Evolution of the Archive.” Queer Cinema, ventil verlag, 2018.

[3] Hubbard, Jim. “A Report on the Archiving of Film and Video Work by Makers with AIDS.” ACT UP, https://actupny.org/diva/Archive.html.

[4] “XFR Collective Presents: Queer Gems from our Leslie-Lohman Residency.” Spectacle Theater, 14 December 2019, https://www.spectacletheater.com/xfr-queer-gems/.