Can I tell you about a woman who, probably five weeks into sheltering in place, when the sky had been as gray at noon as at dusk for days, began to panic because she’d lost her sense of time? She had spent most of that grayness sitting in the same room, looking at the same websites with the same technology, and glancing up at the same featureless sliver of sky. One evening, the imprecision and repetitions that marked her existence caused her to dissociate.

I’d dissociated before, for reasons that were much the same yet totally different, which made the experience even more terrifying. And that’s where my ability to articulate it ends.

As I was taking stock of the one-year anniversary of the pandemic a couple months ago, the memory of this woman vividly returned to me. I savored the bitter irony that homes, which have always been workplaces, had finally gained wider recognition as such, but only because offices were closed. I relived with rage all the times I’d been told that images of domestic interiors are “coded as female”—a statement that is alternately true and untrue, reductive and expressive, and often a wildly sexist, racist, and classist oversimplification of home. I picked through my ceaseless anger, which flowed like a broken faucet whether I was in my coded-as-female space or at my “real” workplace, and where all sizes of disasters, inhumanities, exploitations, and negligences swirled. (The refusal of Western powers to relinquish vaccine patents and develop generics later turned this fury into a firehose.) I realized how badly administered public health measures had disassembled social boundaries to a far deeper extent than covering your nose and mouth with cloth, and how these changes had moved all of us into a kind of exile, wherein we were at home—to be read in the ’90s movie-trailer-man voice— “in a world with a whole new set of rules.”

Except that I’m entirely serious and I can’t hide behind irony anymore, even though the juxtaposed sentiments that comprise irony so perfectly encapsulate this moment and its absurdity and cruelty—not unlike the way the blur between cinematic nonfiction and fiction more precisely expresses the realness of what’s being depicted.

The collective yet unspoken sense of not being at home while at home—of dislocation and the experience of disparate feelings at the same time—put me in mind of some of the great female filmmakers whose work has explored the meaning of home while in exile: women who have refused to provide tidy sentiments about or impose certainties onto something as expansive, illusory, and taken-for-granted as the everyday, and who would agree and disagree and hate-that-they-agree with the “interiors = female” formula. I thought of Trinh T. Minh-ha’s Surname Viet Given Name Nam (1989) and Marilu Mallet’s Unfinished Diary (1982), both by filmmakers from countries in the global South that were brutally reshaped by U.S. anticommunist interventionism. Each film explores how the domestic can be strange—at once your own and not—during exile, and how this uneasiness and non-belonging connect to both the filmmaker’s native and adoptive societies. Though made in very different contexts, these documentaries speak to the unresolved contours of our pandemic experience.

Both films also use deceptively loose, associative structures that reveal them to be constructions—though even after this unmasking, the films’ true shapes remain ambiguous. (Or, perhaps, require more than one viewing and some outside reading to discern.) Surname Viet Given Name Nam uses three major formal strategies, the first of which is cunningly similar to, yet wildly different from, typical documentary voice-of-god narration. Black-and-white found footage (of an indeterminate vintage) of Vietnam, much of it slowed down to the point where you can see the frames flash by, is accompanied by a calm, American-accented voiceover that discusses the incredible feminist poetry of Hồ Xuân Hương, The Tale of Kiều, and other Vietnamese literature. The narrator also examines changing conceptions of national identity, jokes, and folk sayings: how these relate to Vietnamese expectations of women, and how women have been treated in Vietnam throughout history. This narration, whose tone varies from matter-of-fact to unrepentantly militant, and the choppy, difficult-to-parse images that accompany it, are tinged with resentment and bitterness. The overarching argument of the sequence is that there is no place in Vietnamese society where women aren’t likely to be exploited and marginalized. Even in the “women’s city” of the marketplace, they are expected to adhere to Confucian ideals of modesty and patriarchal obedience, and abide by the state’s stringently enforced social controls and food shortages.

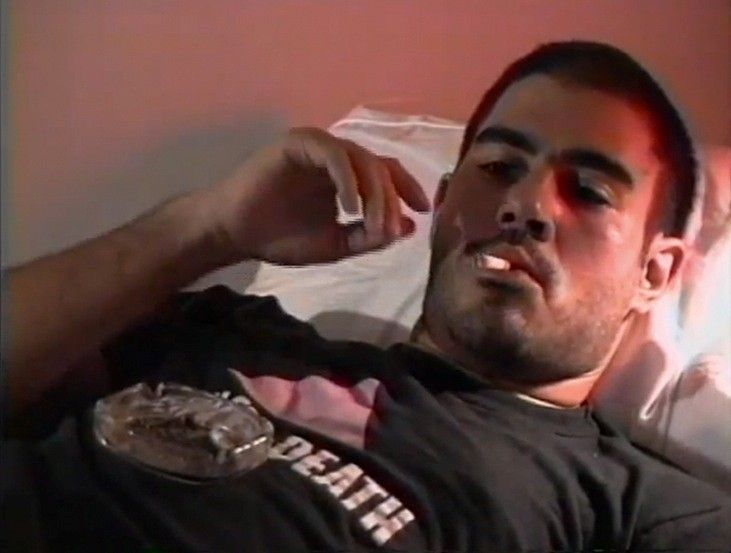

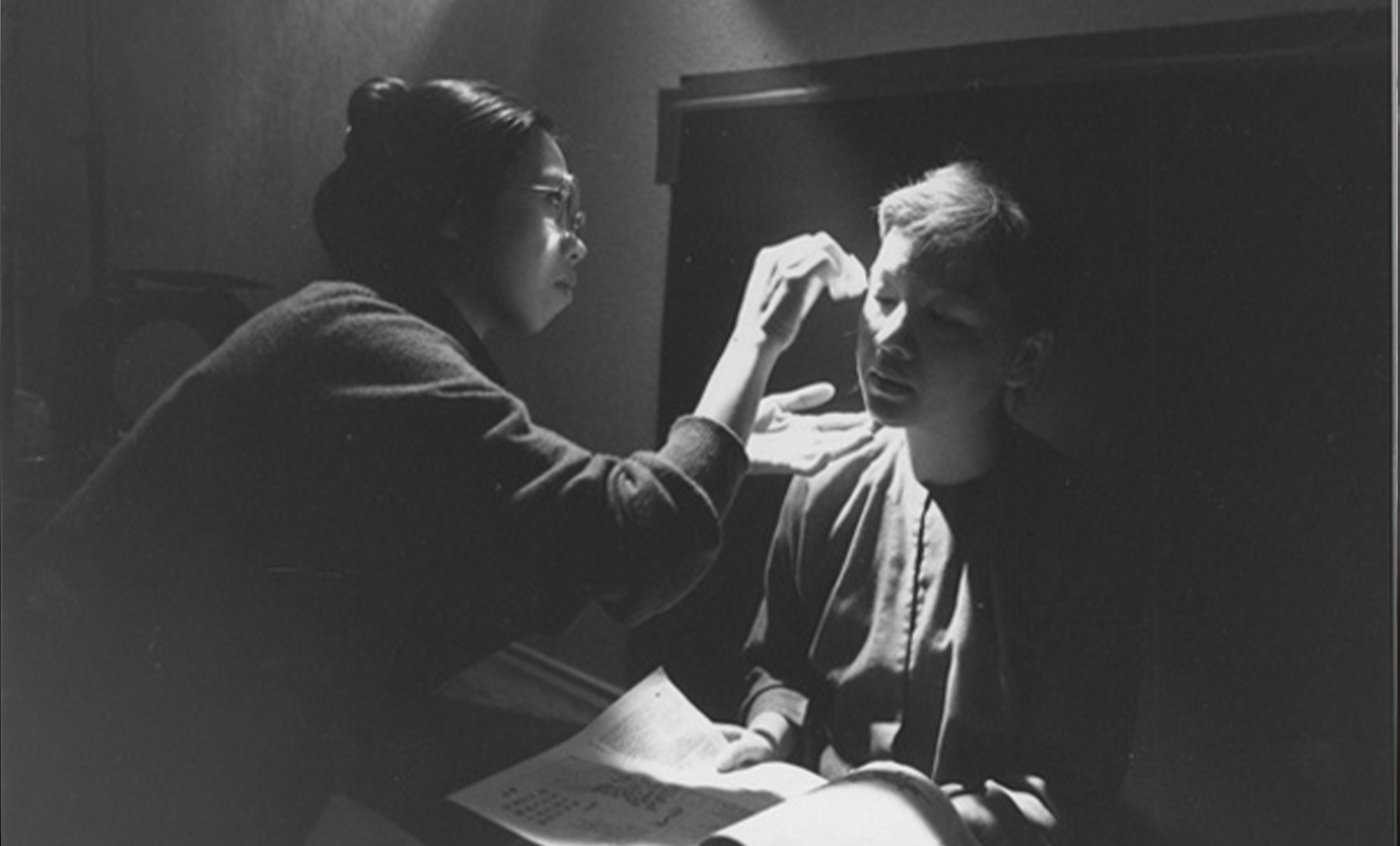

The second strand of Trinh’s approach involves testimonies from female doctors and nurses from Vietnam—professionalized caregivers; healers and performers of emotional labor; women who, unlike in the Vietnam War footage Trinh uses elsewhere in the film, are not running from American forces while wearing rags and carrying children. At first, these are presented as straightforward talking-head interviews. The women speak eloquently of the exploitation inherent to socialist and capitalist systems, the difficulties they face when performing their jobs, the Vietnamese government’s repressive tactics—but they speak in English, oftentimes softly, requiring a viewer who is unaccustomed to a Vietnamese accent (or to low volumes) to lean in and listen especially carefully. This sense of import is bolstered but also complicated by the text Trinh inserts before the interviews or occasionally superimposes over the interviewees’ faces as they speak. One can fall into a false sense of security, following the words on screen as if they were subtitles, only to discover that they don’t necessarily line up with what the speaker is saying or what you thought she had said.

This approach, paired with the fragmented nature of the compositions and the use of the frame to truncate objects, is driven home by testimony that first is spoken and then appears on screen as text, attributed to a Thu Van: “There is the image of woman and there is the reality. Sometimes the two of them don’t go well together.” Perception, both cultural and experiential, is upended as Trinh plays with stereotypes. Her interlocutors speak about being Eastern women (with varying degrees of militancy), and sometimes adhere to norms of how an Eastern woman “should” speak. It’s unclear if we even know their real names, or if the women speaking on screen are the same as those quoted in the title cards that precede their appearances. This elusive sense of self, visually echoed in Trinh’s tactic of showing parts of the women’s bodies but never their entire person, ensures that they remain uncaptured by a Western anthropological gaze, which so often leers and patronizes under the auspices of “learning.” Many women allude to spending time in reeducation camps or being relocated, yet their specific crimes against the state or communism are never provided. (The fieriest speaker is a woman from the less communist South of Vietnam who complains about the Communist Party’s treatment of women and its failure to fully adhere to socialist ideals. At one point, her vocal track fades out before she can finish speaking, and the on-screen text reads, “I am a survivor with no society model.”)

The women are elegantly framed and seem to be speaking from inside their homes; a curtain flutters as a doctor tells the camera, “We receive our patients in a cold, large hall, in the presence of the officer in charge. It’s very difficult to establish trust. How can a woman disclose her intimate sufferings when there is no intimacy to preserve professional confidences?” Yet late into the film, Trinh unveils her third gambit when she shows one of her subjects kneeling in prayer on the floor of a room, describing how “Truth is not always found in what is visible. . . . Woman’s liberation? You are still joking, aren’t you?” Trinh then cuts to a close-up of a picture of the Pope and then zooms out of it, revealing it to be part of some religious art. The camera then pans across the room to show black-and-white family photos. For the first time, we’re in a real living room.

During this slow unmasking, the director offers a definition of an interview: “an antiquated device of documentary. Truth is selected, renewed, displaced. And speech is always tactical.” The narrator begins asking the director questions about her process as we learn that the women we’ve been listening to are untrained actresses who live in the United States. Trinh then explores their lives in their own spaces—one of them is the only female and only Asian engineer at a hydroelectric plant; another is seen speaking to her mixed-race son’s elementary-school class about traditional Vietnamese clothing—as well as the confident second-generation immigrant who performs the voiceover. The film’s compassion grows instead of receding: you see how the women struggle with racism, sexism, and poverty in the United States. Capitalist society has served them no better than the communist state they escaped; as Thu Van says earlier in the film: “Between these two ways of exploiting me, it is difficult for me to choose.” Trinh’s decision to fragment her subjects’ lives and testimonies frees them from servicing the ethnographic eyes of a Westerner (who might expect a neat, three-act structure that builds toward a coherent theme), and from illustrating the Confucian model of a woman who has survived communism’s overhaul of Vietnamese society.

Mallet’s Unfinished Diary wrestles with what it means to have two bad choices and be forced to live with one. Mallet, a Chilean filmmaker and author who fled Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship, lives in Montreal. She is married to an Australian filmmaker (credited as Michael Rubbo, though his name is never spoken) who only speaks to her in English, and has a son who doesn’t speak Spanish. Over the course of the film—whose fictional sections are shot in the same style as its documentary portions, blurring the two modes—Mallet goes about her everyday routine, caring for her son and arguing with her husband while the camera trails her, and sometimes commuting to work in order to shoot interviews for a television documentary in which a female Chilean exile reflects on her experiences in Canada. (One of these expats is Isabelle Allende, daughter of Salvador, who sits in Mallet’s kitchen and recounts the last time she saw her father on September 11, 1973, and how he asked the bombers to wait for his daughters to leave the presidential palace before beginning the bombardment.) Mallet rarely speaks outside of her house, and is more frequently spoken to. “I feel like I don’t participate in society,” she tells her husband. “Maybe you’ve had enough already,” he responds, possibly genuine in his attempt to comfort her but condescending nevertheless. Her self-professed lack of connection with the world around her (she moves silently through her house, the mall, long cab rides) and her increasingly irksome relationship with her husband are amplified by quiet, aimless scenes. The vignettes of her life aren’t arranged in a way that seems to progress toward a larger story or an argument—a style that mimics male sexual release with its rising action—but are instead focused on sensation and emotion. Mallet and her husband’s push and pull gradually become a part of the film’s form, such as in a party scene where other Chilean refugees gather at her house, improvising limericks about Pinochet and a fellow exile who was deported because he couldn’t produce the correct documents. After it’s over, her husband tells her what she should’ve filmed instead of what we’ve just seen, revealing that what has so far resembled a chronological, fly-on-the-wall documentary is, like any other film, a construction. He insists that she stick to a form more suited to a nature documentary than a first-person account, and she begins tearfully yelling at him.

The most profoundly lonely scenes in Unfinished Diary are the silent dolly shots of the inside of Mallet’s home, with the camera gliding through empty hallways and rooms. At first, they seem to be purely impressionistic images of the ennui of a housewife, but as they’re repeated with increasing speed, they start to feel like the point of view of someone rushing from one room to another, futilely searching for something. Yet the art on the walls—which includes framed movie posters for Letter from an Unknown Woman (1948) and Lucia (1968), as well as a terrifying print by Mallet’s mother featuring four grotesque heads that represent Chile’s military leaders—makes one wonder if this is the natural state of Mallet’s house or if it has been dressed for the film. As the fights with her husband grow nastier, touching on filmmaking and the impossibility of certain cultures to connect with one another, their house starts to feel less like a prison and more like a place that has lost its purpose and meaning. But then her husband’s final line, which he delivers directly into Mallet’s camera while standing in front of a wall of tribal masks, muddies which parts are fiction and which parts are documentary preceded it into question. “What? Do you want the true situation now or the…? What?” he asks in a bruised, humiliated tone. After a pause, presumably so that Mallet can give him direction, he responds: “And now we’re probably going to get a divorce.” She abruptly, comically cuts away from him, and he disappears from the rest of the film.

Has everything been a lie? Is this her husband, or just an actor approximating her real or imagined spouse? Are these even Mallet’s true struggles? Like Trinh, Mallet shatters any sense of traditional ethnography. Not only has the process of identification been subverted by both filmmakers, but its component parts—on the level of narrative, performance, mise-en-scène, shot composition, and on-screen titles—have become visible to us. Despite the deeply personal and traumatic aspects of what we have watched these women express, we are denied the pleasure of feeling as though we’ve fully understood them or even the parts of their lives we’ve witnessed. This disjunct—the ground shifting beneath our feet yet remaining the same, the estrangement from anyone who hasn’t lived it the way we have, the broken connection to future generations—finds clear parallels in our own demi-exile of the pandemic. Unfinished Diary and Surname Viet Given Name Nam are neither documents of hopelessness nor guides for resilience, but realistic depictions of living without control. Our homes have never been our own, nor will they ever be.

***

Violet Lucca is the web editor of Harper’s Magazine and hosts its podcast. Her writing has appeared in the New York Times, Criterion’s The Current, Film Comment, Sight & Sound, Caiman de Cahiers du Cinema, and elsewhere.

Stills from Surname Viet Given Name Nam (1989) and Unfinished Diary (1982). Courtesy of Women Make Movies.