I.

As I suspect is also true of countless other nonfiction filmmakers—including those who feel the need to furnish their films with more romantic, star-crossed origin stories—I first encountered the subject of my most recent film on Wikipedia.

The film, Lasting Marks, details through personal testimony and a wealth of archival material the social and political undercurrents of Operation Spanner, an infamous British police investigation into same-sex male sadomasochism. The case began in 1987 and came to trial in 1990, whereupon it set a precedent in British law that effectively criminalised heavy SM.

Wikipedia’s account was less concerned with the societal factors underpinning the investigation than with what it claimed were the case’s lurid beginnings:

The police had obtained a video which they believed depicted acts of sadistic torture, and they launched a murder investigation, convinced that the people in the video were being tortured before being killed. This resulted in raids on a number of properties, and a number of arrests. The apparent victims were alive and well, and soon told the police that they were participating in private BDSM activities.

The entry went on to detail how, upon realising that no murders had taken place, the Obscene Publications Squad of London’s Metropolitan Police nonetheless pressed on with their investigation, ultimately prosecuting 16 men for the consensual “assaults” documented on the videotape.

Having long been fascinated by the relationship between sex and its depiction on screen, this struck me as an irresistible case study. Not only had the authorities mistaken the performance of fantasy for reality, but they were so convinced by their (mis)interpretation that they persevered even once its inaccuracy became clear.

In hindsight, the red flags in that version of events are glaring. Though the Wikipedia entry elsewhere called Operation Spanner “controversial” and alluded to the role of homophobia in the case, the narrative of the mistaken murder investigation offered one of two conveniently exculpatory portraits of the authorities: either they were naïve enough to confuse consensual SM for homicide, or else the activity in question was so extreme that any reasonable person would have come to the same conclusion.

Across 67 words and multiple outlandish claims, the tale was also absent a single citation. Instead, the entire article was littered with what Wikipedia editors call “weasel words”: words or phrases aimed at conveying authority without providing actual detail. How exactly did the police “obtain” the video? What was the “number of properties” raided and the “number of arrests” made?

II.

Finding out proved no small task when I began work on Lasting Marks in 2016, though the timing at first seemed fortuitous. British law requires that various public records be made available to the public after 20 to 30 years, and the files from 1990 had just been released.

However, when I sought out the trial records, I learned that they had been resealed for a further 55 years. Two exemptions were cited to justify this drastic extension, the primary one being “Health and Safety.” An identical justification was given by the Metropolitan Police in denying my FOIA request for their own files on Operation Spanner.

A Met representative argued that the descriptions of SM contained within the files were “quite upsetting in parts and would be likely to be considered distressing to other members of the public.” When I pointed out that a Health and Safety exemption requires that “the disclosure of information might lead to a psychological disorder or make mental illness worse,” the officer changed tack, substituting various other exemptions until I’d exhausted my appeals.

The mainstream press coverage I was able to turn up did at least clarify how Wikipedia’s sensational account had taken shape. To my surprise, it seemed that the backbone of the story—the claim that Operation Spanner began as a murder investigation—was based on a single minor detail that made its way into contemporaneous news reports.

After seizing four homemade SM tapes during an unrelated search and seizure, the police mounted a series of raids on the homes of those featured in the videos. Sniffer dogs were in attendance at one raid, and though they found nothing, their presence was noted during the trial, with the prosecution darkly intoning that the police “thought they might find something awful in the garden, but thankfully they didn’t.”

The defence questioned the relevance of this anecdote, reminding the judge that “the world’s press is listening.” As predicted, the tidbit did appear everywhere from Britain’s notionally liberal broadsheets to its gleefully reactionary tabloids, with The Sun making explicit what the prosecution had left implied: “Some of the films were so violent that police first suspected they had stumbled on a ring killing its victims for snuff movies.”

Without any way to evaluate the tapes for themselves, the public could only take the papers’ word for it, as the papers in turn took the word of the prosecution. Today, the logic is even more circular: in citing “Health and Safety” concerns to block the release of information about the case, the Met invokes the alleged extremity of the men’s behaviour to prevent outside scrutiny of that very claim.

III.

A deeper understanding of Operation Spanner only began to take shape for me thanks to the archival instincts of members of the public. From the beginning, I’d been eager to locate a transcript of the trial itself, to fill in the negative space around the salacious tabloid pull quotes. In the UK, court transcripts can be commissioned by the public, from audio recordings provided by the court to accredited transcription firms. Unfortunately, the tapes in question had been destroyed seven years after the trial, as apparently is the norm for all but the most exceptional cases.

It was only while browsing the personal files of former Gay Times editor Colin Richardson, housed in the LGBTQ-focused Hall-Carpenter Archives, that I miraculously stumbled upon an unlabeled manila folder containing a copy of the transcript, which had been faxed to Richardson three decades earlier.

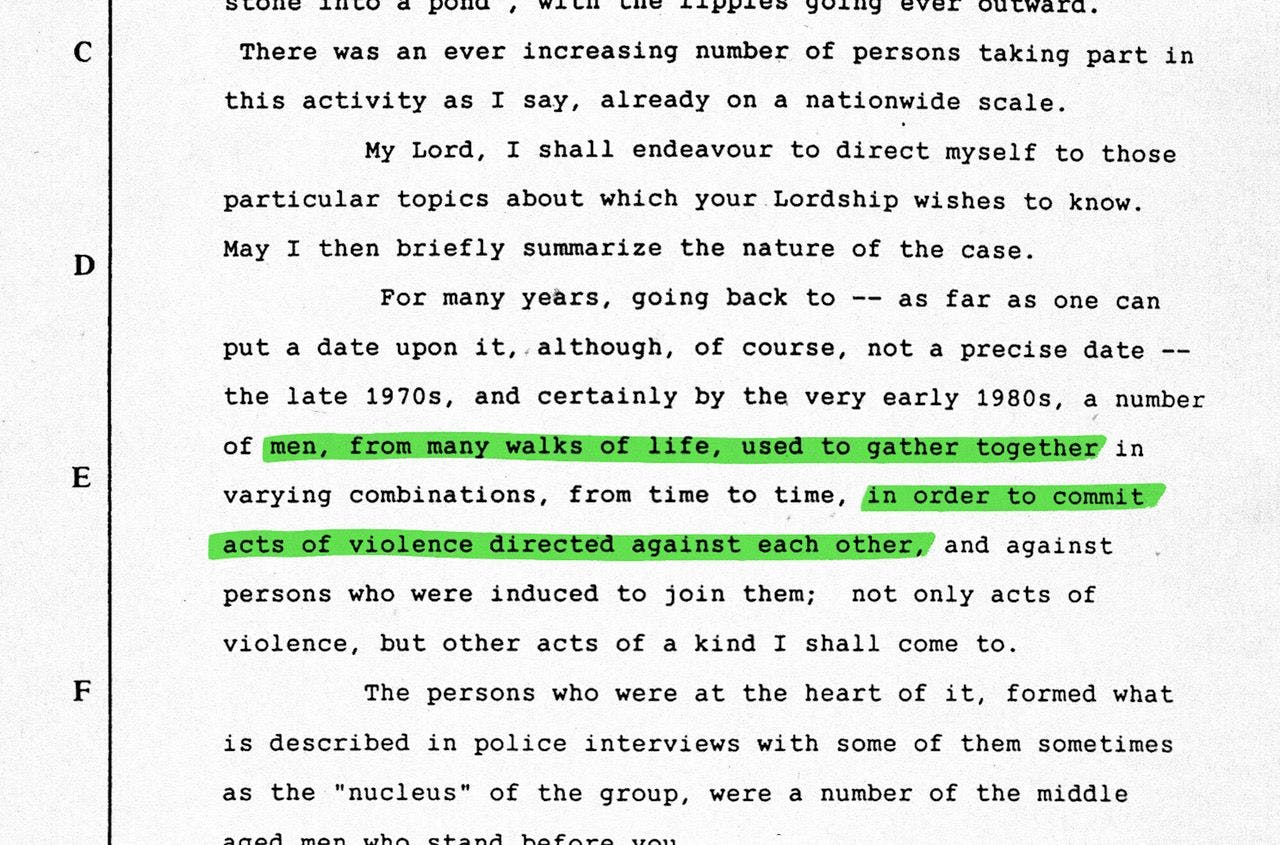

The transcript laid bare the facts of the case and threw into question the motivations of its architects. Just a few weeks into the investigation, on November 4th, 1987, several of the police’s targets willingly submitted to questioning, during which they explained the nature of their private, consensual SM group. Officers repeatedly enquired as to whether anyone was drugged or otherwise coerced into taking part, but could find no one who was. They also failed to find proof that the tapes had been distributed beyond the group, a prerequisite for obscenity prosecution. Nonetheless, the Obscene Publications Squad pressed on for a further three years, at an estimated cost of £2.5 million.

Such prosecutorial zeal is hard to fathom, unless the squad viewed Operation Spanner as a test case, designed to expand its powers. Juries in traditional obscenity cases were famously mercurial, and could not be relied upon to agree with the government on whether material had a “tendency to deprave and corrupt,” as the law required. If a precedent was set that sadomasochists could instead be prosecuted for assault—in spite of the consent of those involved—there would be no need to meet the slippery definition of obscenity in such cases.

Even though assault charges are typically dealt with at a lower magistrates’ court, journalists were briefed as early as March 1988 that the case was likely to be heard in Crown Court, where legal precedent can be set. When finally charged the following year, the defendants were surprised to find themselves facing conspiracy charges alongside those they had expected. Such charges are difficult to prove, but crucially, necessitate that a case be heard in Crown Court. Once the trial was relocated, all claims of conspiracy were summarily dropped.

Of course, there were those who viewed the state’s case with suspicion at the time, Richardson included. In a lengthy article for Gay Times titled “Myths, Half-Truths and Fantasies,” he laid out the inconsistencies in the Met’s version of events, and forced Detective Superintendent Michael Hames, head of the Obscene Publications Squad, to admit that he could not explain how homemade SM tapes had been mistaken for snuff films by a police force that claimed expertise in such matters. “It was just that the activities were so, er, bizarre,” protested Hames, “that, you know, it was regarded as being beyond the pale.”

Publications like Gay Times aren’t available in mainstream newspaper archives and their reporting could not hope to have the same kind of impact that tabloids did on the public understanding of a case like Operation Spanner. It was my hope that Lasting Marks could do justice to the risks they took in cutting against the grain of popular opinion, by now placing the prosecutions in their proper context.

IV.

As the film began its tour of the festival circuit, it was written about in numerous outlets, and I hoped these mentions might elevate its standing among the sources vying to define Operation Spanner and its legacy. Again and again, however, the film was described not with reference to its actual content, but with inaccuracies lifted directly from Wikipedia.

The situation grew only more frustrating as I prepared to launch Lasting Marks online in partnership with The Guardian. In an unrelated article about the gay leather scene, the newspaper described Operation Spanner as “the high-profile conviction of gay sadomasochists arrested in Manchester.” In fact, of the 16 men charged, not one lived or was arrested in Manchester. Where a reference to the city did appear, without citation, was in the opening line of the case’s Wikipedia entry.

I realised that Lasting Marks’s impact on the popular conception of the case would always be limited as long as Wikipedia’s web of misinformation remained any curious mind’s first port of call.

The deference afforded to the site is understandable: for all its flaws and biases, it’s inarguably one of the internet’s most valuable resources. A freely licensed, collectively edited guide to (potentially) everything, it’s nothing short of a miracle that the site has remained un-co-opted and uncommodified since its creation in 2001. At its best, it’s living proof of the wisdom of the crowd, and a vital counterpoint to the official repositories of our history, which—as my research confirmed to me—often fall short of the task.

And so, in order to put my work on Operation Spanner to bed, I set about rewriting its Wikipedia entry from the ground up. Some of this was relatively straightforward. Two years of research had given me access to specifics where the entry had offered only vague generalizations: the number of men named in the Obscene Publications Squad’s report: 43; the number whom the government elected to charge: 16; the longest prison sentence handed down by the judge: four and a half years.

More complicated were those assertions that hewed closer to a subjective judgement. It’s my opinion that Operation Spanner was a homophobic project, and this opinion is expressed openly and directly in Lasting Marks. On Wikipedia, such assessments—at least when divorced from verifiable facts—are thorny, and may contravene the website’s neutrality policy. But what exactly would verify a prejudice, beyond an admission from the horse’s mouth?

The investigation occured at a turning point for the Obscene Publications Squad, which had once been relatively open about whom, and for whom, it was fighting. In October 1987, the month that Operation Spanner began, Hames’s predecessor Superintendent Iain Donaldson spoke publicly of facing down “a very powerful lobby that [says] homosexuality is normal and should not be discouraged.”

By the time the case came to trial, however, Hames had instituted a more media-savvy regime. He began attending a quarterly forum on the policing of London’s lesbian and gay communities, and strenuously denied that the squad’s flagship operation was a homophobic one, telling the group: “These were very extreme sadomasochists. Their homosexuality was merely incidental.”

In court, the government seemed less inclined to elide the men’s sexual orientation. Prosecutor Michael Worsley QC characterised their behaviour as "brute homosexual activity in sinister circumstances, about as far removed as can be imagined from the concept of human love" and said it was “worth mentioning” that some of the defendents were HIV-positive. These made for illustrative details as I reworked Wikipedia’s understanding of the trial.

Just as importantly, I documented the ways in which homophobia permeated the case from the outside. In 1987, a study found that three quarters of Britons thought homosexual activity was always or mostly wrong. That same year, a scaremongering public information campaign on HIV/AIDS was plastered across billboards and TV stations, while Margaret Thatcher made her opposition to LGBTQ education a pillar of her reelection campaign, decrying the “hard left education authorities” who she said taught children “that they have an inalienable right to be gay.”

Citation by citation, I built a case that the tail end of the 1980s represented a uniquely sharp inflection point in the backlash against gay rights in the UK, and that Operation Spanner should be viewed as symptomatic. This framing, while based in fact, is of course subjective, and an editor seeking to justify the operation might (just as permissibly) present the various accidental deaths that have been linked to sadomasochism as critical background information. Given enough time, either of these diametrically opposed narratives could harden into the accepted “truth” of the case.

V.

Public faith in Wikipedia is built on the trust that bad information will eventually be supplanted by good—even if that’s far more likely to occur with the fiercely debated entries on European capitals, U.S. presidents, and minor Star Trek characters than on the scant pages dedicated to female academics, histories of the Global South, or homophobic police operations from 30 years ago.

Perhaps this explains why Wikipedia’s article on Operation Spanner—be it my painstakingly researched 3400-word version, or the entry written seemingly from memory in 2004 that went largely unaltered for more than a decade—is likely to be called upon with greater regularity and reliance than any documentary on the case.

I don’t subscribe to the most pessimistic view of nonfiction filmmaking, which holds that the form is inherently impotent, but I do think that real “impact”—to use the dreaded word that has launched a thousand documentary funding applications—is almost vanishingly rare. In a bracingly unsentimental 2017 article for Filmmaker Magazine, programmer Chris Boeckmann wrote that in five years of screening social issue documentaries, his primary impact—so to speak—had been to prop up the “myth that this pervasive, pedantic sort of documentary can change the world.”

I can’t help but think that this routine inefficacy has something to do with documentary’s readily apparent subjectivity. Blackfish is perhaps the most impactful nonfiction film of the last decade, having dented SeaWorld’s revenue by tens of millions and halved the company’s stock price, and even then, SeaWorld was able to limit the damage by labeling the film “propaganda” and questioning the motivations of its creative team, techniques I suspect would’ve proven even more successful in the Trump era.

Meanwhile, Wikipedia’s many articles about the company’s scandals and skeletons live on. An encyclopedia with 1.5 billion readers and no named authors is a trickier target for character assassination.

As an artist, I feel committed to exploring the subjective nature of truth and the effect our prejudices and preconceptions have on our understanding of a common event. At the same time, I’ve never felt more alive to the limits of that exercise, and the need to participate directly in the theatre of “objective” truthmaking, on Wikipedia and beyond. The responsibility for telling the story of the past is simply too precious to be surrendered to the forces of reaction and entrenched power. History will be written one way or the other.

***

Charlie Shackleton is a filmmaker and sometime film critic, best known for the feature-length essay films Beyond Clueless and Fear Itself, as well as the award-winning short films Fish Story and Lasting Marks. His latest project, A Machine for Viewing, was a part of the New Frontier program at the 2020 Sundance Film Festival.