Field Notes is inspired by the many independent initiatives worldwide that have responded to the need for critical, considered, and independent writing on nonfiction. To kick off our first issue, Contributing Editor Devika Girish spoke with the creators of two such initiatives: Rooney Elmi, the founding editor of SVLLY(wood) and co-founder of the No Evil Eye microcinema; and Matt Turner, marketing manager at Open City Documentary Festival and founding editor of the Non-Fiction journal.

We hope that their invigorating chat—which touches upon the intersections of form and subject matter in documentary, the mode’s exploitative and colonialist legacy, and the need to create sustainable spaces for writing—functions as a sort of “mission conversation,” in lieu of a traditional, monolithic mission statement.

Note: this conversation has been edited and condensed for length.

***

Devika Girish: Matt, you've been working at a documentary film festival for a little while, and earlier this year you started a journal called Non-Fiction. What incited this project?

Matt Turner: I do marketing at Open City Docs, and for a number of years, we've commissioned short texts to go with the films in the program. We thought there was an opportunity to expand that and to detach it from the festival and the prerogatives that come with it. We also identified a paucity of available spaces for writers to write in interesting ways about nonfiction and for artists who make work in that mode to receive serious treatment. The journal itself is quite straightforward, in that it is a biannual publication for nonfiction writing of any kind, on any form of media, new or old, without the usual limitations that might prevent a film publication from taking that writing in more interesting directions—such as the need to write about films that are coming out or included in a festival, or which have a topic that drives what editors think their readers want. We conceived this journal with the specific aim of providing a space for articles that might not find a home elsewhere. And it seems to be going good so far—our second issue comes out November.

DG: And Rooney, your magazine, SVLLY(wood), is not dedicated just to nonfiction, but it gives a lot of space to that kind of work. And No Evil Eye, the microcinema that you've co-founded, has also been a showcase for nonfiction work, especially by Black, Brown, and indigenous filmmakers. I remember attending No Evil Eye's New York screening about a year ago. It was an utterly eclectic mix of works—from shorts made by young directors to films that have shown at festivals. But they were all very engaged with contemporaneous questions around borders and immigration.

Rooney Elmi: Yeah, that was Sequence 01, which we're still touring, and it was on the theme of diasporic reckoning through the prism of landscapes, memory, and migration. I got interested in nonfiction in my early 20s, when I was still a college student. I was a political organizer and it felt bankrupt for me to not engage with works that were also discussing political topics, especially on an international level. I really do think that documentary is producing some of the most exciting work in contemporary visual media. There is a combination of pioneering aesthetics and social commentary that blurs that line between the personal and the political. Both SVLLY(wood) and No Evil Eye don't primarily situate themselves as arenas for nonfiction, but they are guided by an intention to engage with an internationalist cohort of creatives and artists who use the camera as a tool to reflect their own spaces and places. And they often do that through nonfiction.

DG: That makes sense. Even after I ventured into criticism, it took me a while to understand what it means to engage critically with a nonfiction film. When I was growing up in India, there wasn't a mainstream exhibition space or culture for documentaries. That space didn't exist in a robust form even on television then. So, as a critic, it’s taken me some time to understand how to situate documentary outside of the journalistic and the ethnographic impulse and consider those in conjunction with questions of narrative and aesthetics. I'm curious if either of you had a specific moment or film that made the idea of documentary as a distinct kind of cinema click into place?

MT: Like many people of our age, I watched [Véréna Paravel and Lucien Castaing-Taylor’s] Leviathan eight years ago, and through watching that and other films like it, gained an awareness that documentary or nonfiction films didn't need to be made in certain ways. And that the form of the film could be at the center of what the artist was thinking about, counter to the prevailing narrative of documentary as a delivery system for the message rather than an artistic object in and of itself that may deal with a subject or a message.

RE: My exposure to what the medium of cinema has to offer came from going to film festivals, which I find a bit depressing. I discovered that there's so much more you can do with the camera as a tool through films that most people don't have access to viewing. That's another reason I wanted to create SVLLY(wood) as well as No Evil Eye, so that there can be some accessibility and transparency around the films and filmmakers that I find interesting.

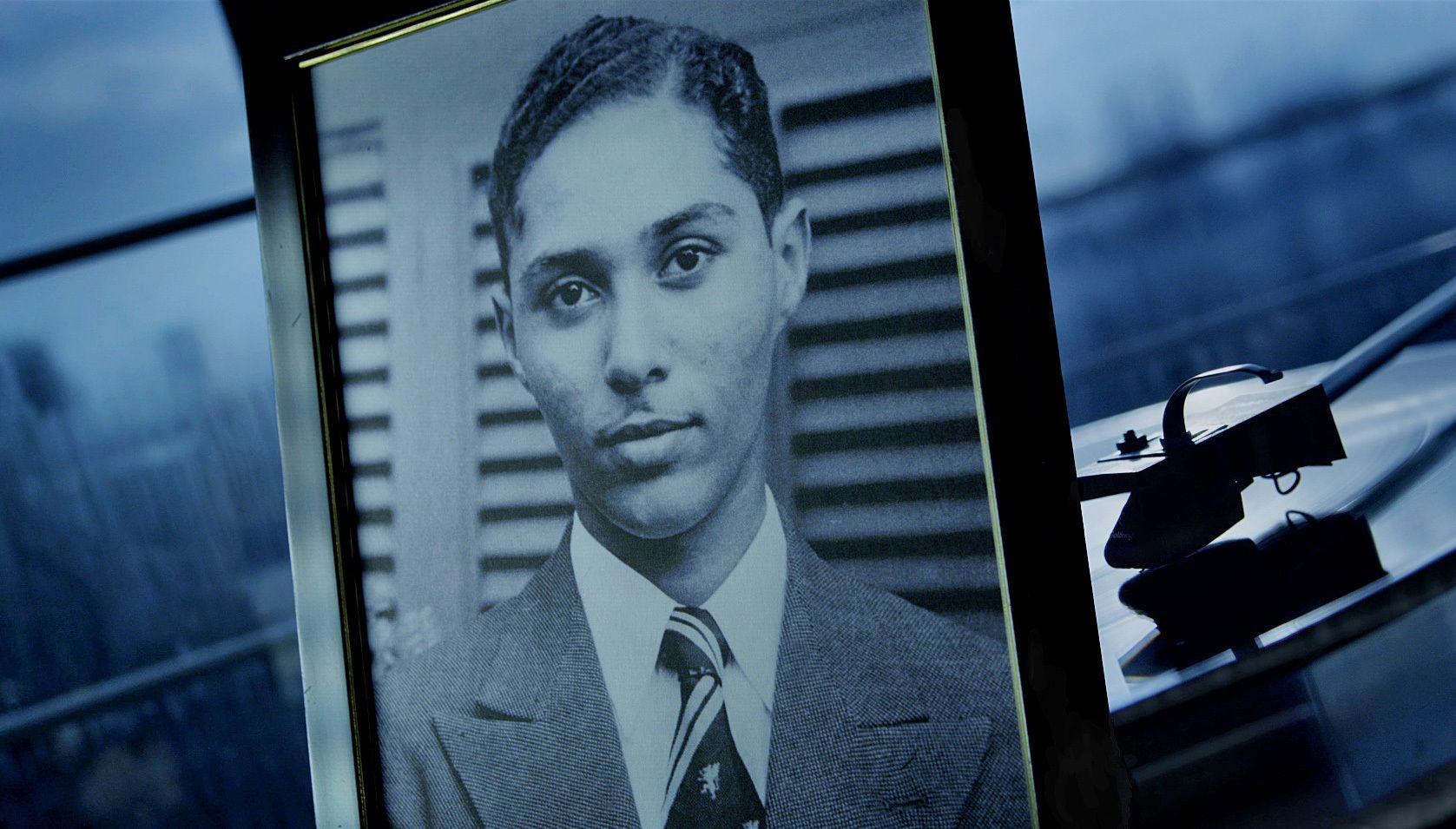

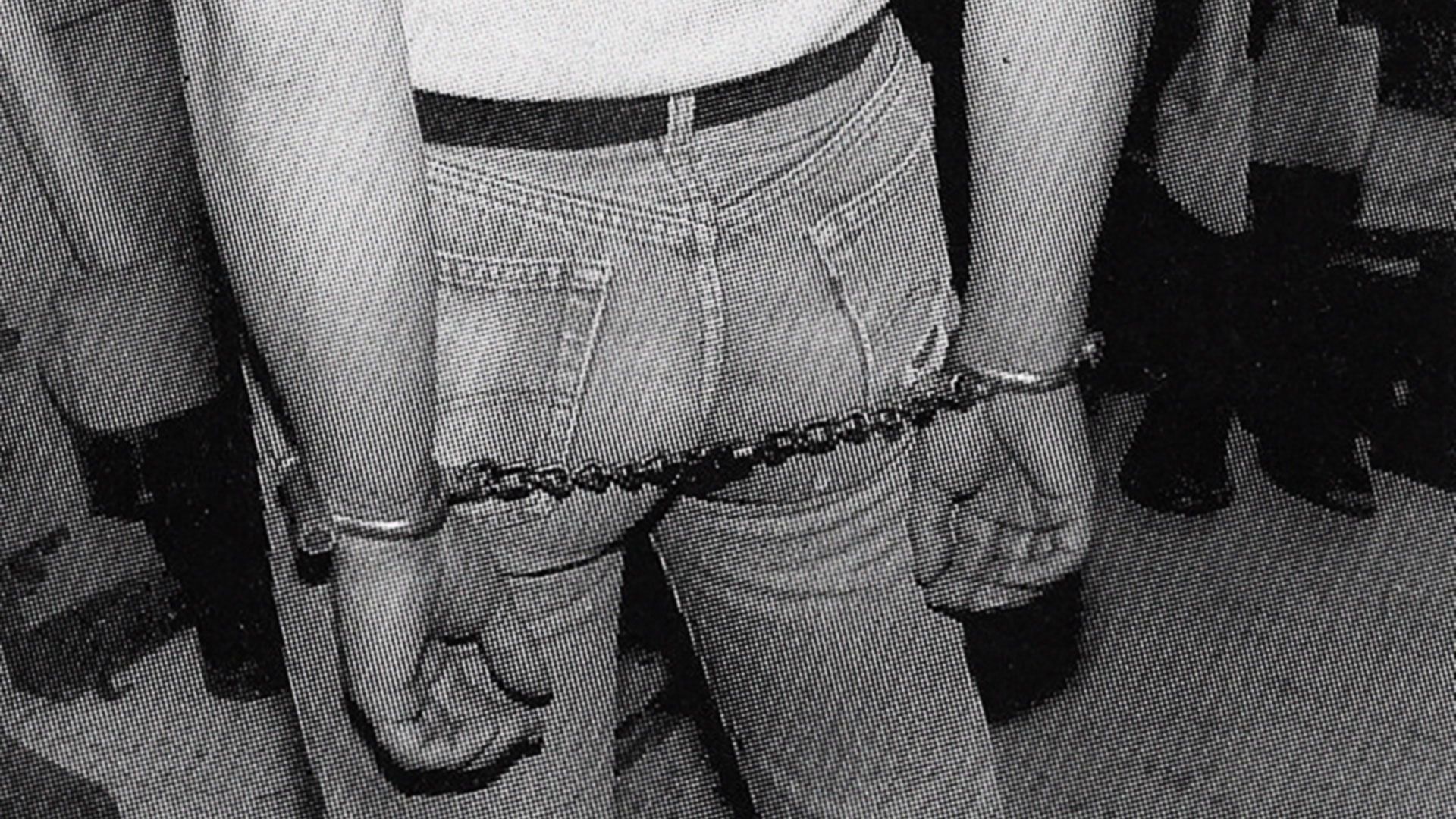

I can think of two films that were formative for me: Kirsten Johnson's Cameraperson and Brett Story's The Prison in Twelve Landscapes. With Cameraperson, there was this woman who just cut and pasted all these clips from her work as a documentarian and told an incredibly personal story through them. And The Prison in Twelve Landscapes is a documentation of the American landscape by a Canadian geographer. She's making a movie about prisons without ever going inside of one. She's critiquing the carceral state without using the normalized exploitative gaze. And when you finally see a prison at the end of the film... That was a shocking moment for me. I said, wow, you can make a movie about whatever you want and you don't have to be exploitative at all. And there’s also the political urgency of Laura Poitras’s filmography, and the poetic, thoughtful, and reflective mother-daughter relationship in Chantal Akerman's News from Home. Those were important to me as well.

DG: Since you mentioned Laura: Citizenfour was really formative for me, too. I encountered it just when I was starting to develop an interest in cinema, in college. I remember noticing that the film had a breaking news kind of urgency to it, but it delivered that with a formal precision and ingenuity that seemed to arise from the circumstances of production—like how much they were able to film, the close quarters in which they did a lot of the filming, the measures they had to take in order to ensure their privacy and safety, which were constantly threatened. There was a precarity in the making of that film that was injected into the form, and I remember finding that to be remarkable.

RE: I always thought it was very cool that this guy, a whistleblower, just decided: "You know who I'm going to hit up? I'm going to hit up a documentarian to tell my story." That was very important for me.

DG: Rooney, you brought up the word “exploitative.” That's a big concern for me when writing about documentaries. Nonfiction filmmaking has historically been a colonialist and ethnographic mode of cinema. The subject-object relationship that characterized those histories is built into the very DNA of the form. Though of course, you have incredible filmmakers who are subverting those ways of looking, whether it's RaMell Ross or Garrett Bradley. In Cameraperson, there is a scene in which Johnson is talking to a young woman at an abortion clinic, and you just see the woman’s hands. I remember that standing out to me because you could sense the intimacy of the encounter between that person and Johnson, the cameraperson. Their conversation goes way beyond that of a documentarian and her subject: Johnson is genuinely talking to the woman. I was struck by what the camera elides and what it focuses on, how it gives you a sense of closeness while still holding you at a distance. I'm wondering how you both confront those dynamics while watching and writing about documentary.

MT: I think those considerations have to be at the forefront when approaching a film. What can be difficult is identifying those dynamics when they're not centered in the film like in the example you just mentioned. And trying to look deeper than the film object itself to the conditions of its production, or how the filmmaker is crediting or not crediting those who were involved, or what the participants are getting from it. You often see a reticence to address these things or to criticize nonfiction filmmaking because of the sensitivities at play regarding the subjects and the people depicted.

DG: As in the case of the “important” film.

MT: The important film, yes. Or more broadly, in activist documentaries for example, what's being addressed and depicted is generally valuable. But I think writers need to be keener to challenge the method of representing it—how it’s been done and to what end.

DG: Rooney, you and I have talked a lot about the fact that documentary comes from a colonial history of viewing and consuming images of the Other, which is a legacy that is still felt in the formal conventions of the mode and the way nonfiction is written about. I'm curious how you grapple with that in your writing.

RE: If I were to take a historical materialist lens, I would say that there is no way to divest the camera from the celluloid legacy of racism and sexism and turn it into a new technology for us to engage with. I do believe that the camera is an incredibly powerful tool. It has historically been used as a tool of propaganda, of colonialism. There are examples of the camera literally coming into certain countries and continents via colonial film units. But I think cinephilia as a culture has never interrogated that power structure and history, which is something that I'm very irked about. I think the only way to use this tool as a medium for thought, education, reflection, and collective memory-making is to give it to the people who've historically been ostracized from it and who have something important to say. I do think it's our duty to vigorously interrogate history so that we can have a much better future.

DG: I took a class on the “aesthetics and politics of cinema” in college, and that’s where I learnt about the history of British documentary and its central figures, like John Grierson. It was later, in a different context, that I read about colonial film units. And I came across an article from 1941 in Documentary News Letter, a magazine founded by Grierson, which outlined the principles of making films for “primitive peoples.” The author of that article, William Sellers, was the first director of the Colonial Film Unit, and he laid out in this schematic and pseudoscientific way what he believed Africans and other colonized peoples were capable of perceiving visually. He has all these rules: You can't use vertical pans because the African will think that the building is collapsing. You can't have more than two things moving within the frame because they can only focus on one thing at a time.

It was remarkable to me that none of this had been touched upon in the class that I took at an American university about the politics and aesthetics of cinema. We studied anti-fascist films like The Spanish Earth as examples of early political documentary, but we didn’t talk about the parallel colonial history of nonfiction, about the fact that racist perceptions and assumptions about the cognitive abilities of different races of people are coded into the very forms of these films. It makes me wonder, do we need a complete revolution for what making images of people and culture can and should look like?

RE: Hell yeah! I think there's a revolution needed on all fronts but definitely when it comes to the moving image. You're talking about a technology that, like I said, came to certain places strictly on the basis of imperialism. And what I find interesting is that when you give this tool to the natives, to indigenous peoples, to people who have been historically excluded from the big screen or the camera itself, there's an immediate need to reflect their own communities and their own sensibilities. I recently gave a talk about Ousmane Sembène, who is considered the father of African cinema. The films that he was watching had always been racist for him and for his peers. But the second you gave that technology to him, it became a completely different form. I'm very enticed by that. There are so many other examples of when you democratize cinematic technology and resources, they become tools of reflection, education, and emancipation.

MT: Your example of learning about that set of rules and codes and the colonialist legacy of nonfiction makes me think of how many other rules, ways of image-making, ways of writing, ways of circulating film have been based on preconceptions that have mutated but ultimately prevailed through the years and come to inform the ways in which we're reproducing those ideas. How many other founding principles have I missed, have we not been told of, which as Rooney says, need to be interrogated more.

DG: For sure. And I came across that little nugget of history in a class on postcolonial studies, not film studies. How do we make these discussions a part of the discussion of cinema? There are two different impulses, as I see it. There’s mainstream criticism on nonfiction that does not center form enough. It fixates on the content and treats documentary filmmaking as an extension of news or journalism. But then you have this other bias in academia and certain hallowed spheres of film writing where the analysis of form seems to be separated from the ways in which it is informed by its subjects historically. I’m wondering, what is the power of criticism here? Are we just exaggerating our capacities? I grapple with that sometimes. Can writing about films actually do something?

RE: That's a big question. We're all just writing to the wind. Nothing matters. No one's reading anyway. [laughs]

DG: I'll add a follow-up to that. First of all, how can criticism intervene? And secondly, it's important to think of criticism also as a tradition and a practice with a historical legacy of its own. Matt, I was looking at the website for Non-Fiction and you have this great line about treating criticism as a type of creation in itself, not just a response. And that brings up other questions of how criticism is also governed by inequities of who gets to write about nonfiction. What sort of conventions are they using? And what historical assumptions are at play in their work?

MT: To your first question, I would be inclined to shrink the objective somewhat to a less grand question, which has to do with occupying a margin and doing what you can within that space versus needing to push a center to do better. It's something I flip back and forth on. Maybe you try something larger, such as your question of great change through criticism, and you see that that's unlikely, so you redefine what you're trying to do and look at the smaller impacts. Which could be that you write a text and it changes the way one or two people think, which changes the way they make films, which then achieves the larger aims you speak of but on a slower scale.

RE: I agree about shrinking the big questions. I don't ask myself: what is the role of a critic? It's just about having a foundation and intention for what I do. I think using criticism as a tool of promotion, not like a publicist, but by talking about the films that you're interested in, that you want other people to know about, and using your scholarship, your sensibilities, your life experiences, and your realities to do so, is incredibly important. Even if it's just one person who reads it and is enticed by the words and begins to question their own tastes or their own gaze upon cinema.

MT: I watched the NYFF panel that you were on the other day, Rooney, on countering canons and creating alternative ways of programming. I’m wondering if we could talk about that in relation to the economics of writing. When people have criticism roundtables, they talk about what criticism should or could do but without addressing the fundamental question of the limitations imposed by the market. What do we see as other ways to write and how can they be made sustainable?

DG: That’s a great point. There are plenty of independent initiatives, zines, etc., but if we're talking about financially sustainable places, then there are very few that seek out in-depth writing about documentary while also being able to support the people who do that work and the time, energy, and research it requires.

MT: That also speaks to the previous point about the lack of historicity and research in the ways that people watch and understand documentary. If you don’t have the remuneration to do that research, it encourages self-compromise.

RE: There's without a doubt a complete lacuna of spaces and places to talk about nonfiction cinema and also be compensated for your creative labor. When I was starting out, I thought, "There are no places to write. No one is going to take my pitches. So I'll just make my own magazine.”

DG: The panel you were just talking about, Matt, which I helped co-organize—one of the panelists, Ajay Ram, a founder of the Upside Film Festival, talked about how you can celebrate their work for being grassroots and alternative and doing things differently, but it doesn’t translate into a paycheck. There are people building alternative structures, but that's not actually helping sustain them. And institutional funding helps, but it becomes a kind of patronage model of waiting for someone who has the capital to give you the space and the money to do your thing. It doesn't challenge the basic structures that we're talking about, which make it so that certain people have the luxury to write and others don't. So how do we create grassroots enterprises that also can sustain themselves?

MT: I’m thinking of the recent online series organized by Abby Sun and Keisha Knight, My Sight Is Lined with Visions: 1990s Asian American Film and Video. When I saw that, I thought, wow, they've got the full package—even if in a specific set of circumstances with specific aims. They've produced this thing in the way that they intended while still being able to remunerate the artists directly, commission essays, and have it be entirely detached from an institutional model that could compromise those original objectives.

RE: I wish there was a clear, succinct answer to this. Keisha and Abby are two incredible, genius people who deserve every penny and more. But then there’s the question of credibility. You have to have skin in the game or cosigns from institutions to get that level of credibility, money, and press.

DG: Or to even get in touch with filmmakers and writers. You need connections.

DG: This is all reminding me of a conversation I had with Garrett Bradley recently. We were talking about how the pandemic has exposed the unsustainability of all systems and perhaps this is an opportunity to build new structures. And I asked her, "How do you think about filmmaking in this context? Where does filmmaking or art-making fit within a radical reworking of the world? How do you locate your purpose?" Because that’s something I’ve been struggling with. And Garrett told me that one of her friends had said to her, “When you're led by your imagination, the possibilities are limitless in terms of what you can contribute.” Someone needs to do the work of imagining things for others to come in and build them.

RE: Amen.

MT: Exactly.

DE: That really helped me because sometimes it feels like filmmaking and writing about film are operating in a very abstract space, and it's not clear how that engages with the world. But abstraction is actually also necessary because we need to imagine things, we need to explore possibilities that don't exist and therefore have to be first worked out in the realm of writing and art before they can be injected into the material world.

RE: I think sometimes we put too much on our plates. For filmmakers, your duty is just to imagine these new possibilities and put them on the screen. And then as programmers, you carry that in a way that's reflective of your communities or of the times. And as writers, you discuss that. It’s important to acknowledge that we don't have all the answers. I'm not even interested in having all the answers. I think there's greatness that comes out of being honest about that.

MT: And there are spaces to do things differently and people should be implored to try even if it doesn't necessarily work. There are different ways to write and think than those that you have inherited.

RE: And if you feel like there isn't a home for you, just create it for yourself.

***

Photos courtesy of Brett Story, Laura Poitras, and Garrett Bradley.