Note: these letters were exchanged by the writers in mid-August and early September.

08.13.2020

Dear Jillian,

Recently, I was reminded of Queen of Lapa (2019): an impressive and intimate piece of verité about the late Luana Muniz, a trans sex worker and cabaret performer living the neighborhood of Lapa in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. The film focuses on her ownership of a restaurant-turned-brothel that she shared with her younger trans sisters. Think: Pietrangeli’s Adua and Her Friends meets the Maysles’ Grey Gardens. I have never before seen such a flamboyant, unhesitant love letter to those within the oldest profession.

One year after first encountering Lapa while screening selections for NewFest, New York City’s LGBTQ film festival, I continue to clutch this epistle to my chest. How were its creators, the Brooklyn-based partner-filmmakers Theodore Collatos and Carolina Monnerat, faring during a moment that has made cinema a far less visceral and materially rewarding experience? A girlfriend of mine once referred to documentary filmmaking as “thankless.” I was incensed at the time, but it’s an observation I now accept during this bloody pandemic, and especially when revisiting glorious, underseen stories like this one.

For the sake of art, love, and epistolary bliss, I will get personal. Two things have kept me firmly rooted to New York throughout my six years of residency here, the key one being the movies. The self-imposed and self-determined “social distancing” of going to the cinema has defined my existence as a film critic—that happy loneliness of it all. Likewise, I have so many stories-within-stories I want to tell you of tangibly experiencing movies in the city: of the kindness of strangers, chance encounters, and the shared, natural language of loving film.

Once the pandemic is over and we begin the work of rebuilding and healing in ways we’ve yet to conceive, I know with the totality of my soul that there will be places—be they basements or bedrooms or backyards—where people will sit, shoulder to shoulder, and consume moving pictures. Given the financial constraints and physical limitations of pandemic filmmaking, these films might be as rudimentary as the Stone Age cave paintings of horses in Europe, but they will still represent the most cathartic experiences I’ve had with movies since at least the middle of March. I desperately miss the unexpected: touch, friction, conflict, chance, hope. And given my critical affinity for experimental and nonfiction cinemas, I am eager to see these new filmic stallions gallop across a bedsheet screen.

The other thing that has sustained my relationship with our city is sex work, specifically escorting. The trade is something I view as ruefully and fondly as I do our nonprofit theaters. There is so much to love and hate about any professional system that compensates one handsomely and swiftly within the parameters of capitalism, but insists upon deeming itself philanthropic. In my case, I find ways to take the good and leave the bad, particularly when the persons with whom I am discussing equity in sex work or cinema know little about courtesans or Cukor.

When you have as many cultural loves as I do, they frequently—richly —begin to neglect you, and instead, court one another. This, if nothing else, explains why I once wrote a story about a lonely metropolitan escort who becomes infatuated with the legendary Italian actress Anna Magnani. In it, she compares the act of buying tickets to a Magnani retrospective to soliciting a prostitute.

I suppose what I ultimately want to explore with you is how, during this moment, it is vital for us to abolish notions of prestige and increase tolerance for the underground—I’d like it if society exited the pandemic with a more humane eye toward sex workers, who now, post-SESTA and post-FOSTA, get by via dark web classifieds. I would also like it if moviegoers reemerged boasting more of an appetite for nonfiction films that risk being written off as amateur, niche, or eccentric.

I can safely presume you share some variation of this same ardency, given that you are an experimental filmmaker whose work has been presented in independent nooks and crannies around the city.

You see, I am concerned that the people who have kept our souls and bodies intact through pleasure and entertainment risk not having anyone to do the same for them. I encourage the voyeurs who enjoy this spectacle of letters to donate to GLITS or another sex worker relief fund as a form of gratuity. One of my many worries at present is that our city’s independent filmmakers (who are perpetually “just getting by”) will not have the chance to be among that ramshackle fold that leads the reshaping of our arts and cultural sector; I want Collatos and Monnerat to be able to continue making work that is grounded in love and reverence for an unknown subject.

Last summer, while wading through the hundreds of submissions for NewFest, I fell madly in love with their first collaborative project. For months, Lapa remained an admittedly tricky film to program and sell. Foreign language. Documentary. Violence against transwomen. Hustling. Not exactly the visual pleasures that a garden variety Park Slope dyke or Chelsea fag is seeking for a Friday date night.

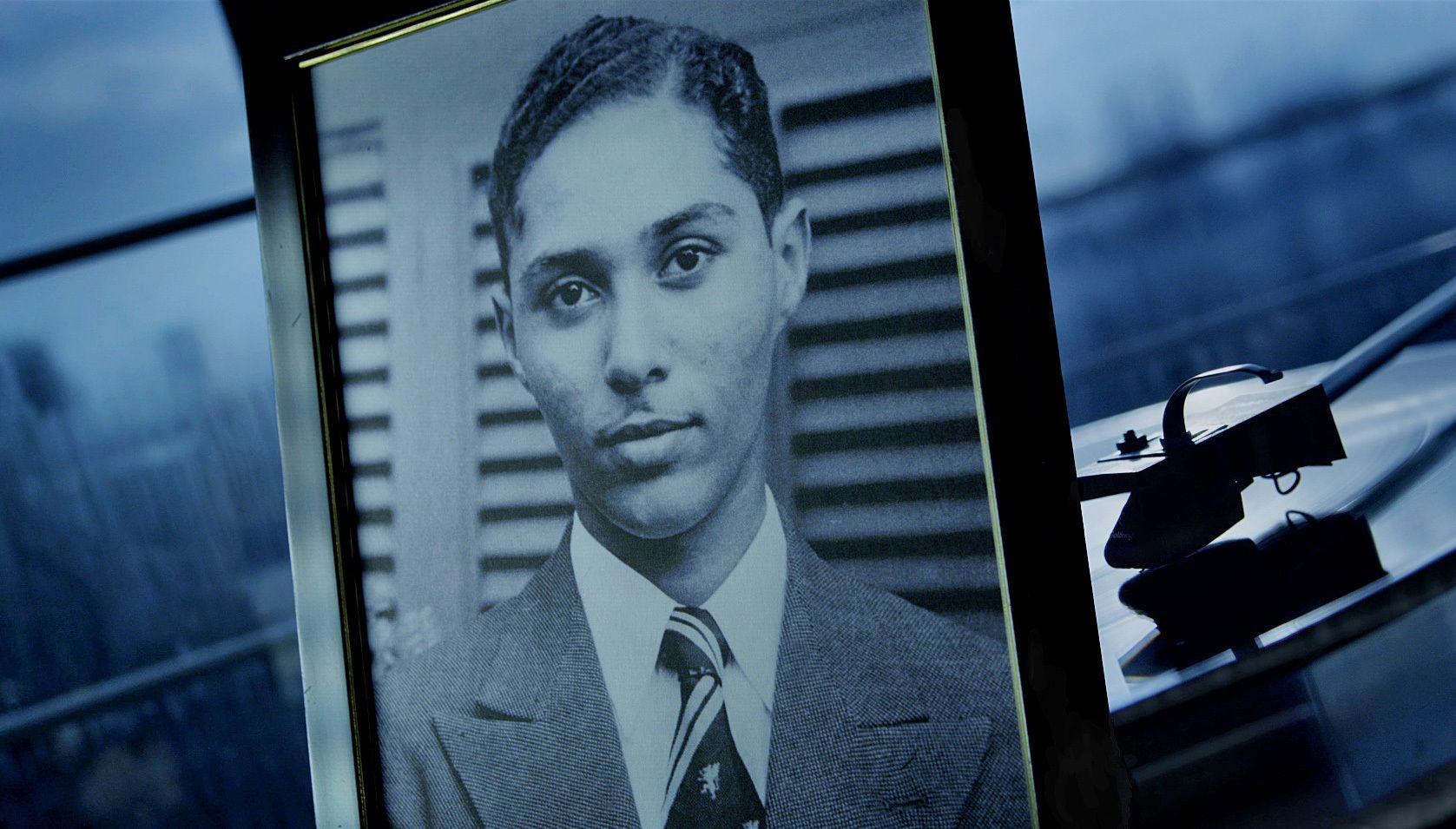

Lapa’s visual architecture resembles its brothel dynamics: everything here is so chaotically good. Sisterhood prevails, but in a tough love, fix your eyeliner and stop bellyaching way we all crave from a magnanimous matriarch from time to time. We enter the home in Rio via the smallest of cameras and remain there for what feels like years. The girls, all trans sex workers, have vast and varied personas, gender confirmation surgery goals, work ethics, and dreams about love: some fall in love with johns quickly; others do not. Luana, who became a sex worker at 11 and died of natural causes shortly after filming concluded, was obviously conjuring the world she wished she had had when at a tender age. The age of consent in Brazil is 14; as a result, several of the girls seem appallingly young. I find it immensely comforting to know that, at the end of the night, Luana was there to afford them a roof, food, and clean linens.

While concerns of exploitation are always present when viewing films about fringe cultures (and especially so with moving pictures about the physical intimacies of sex work and queer life), Luana Muniz clearly knew what she was doing by letting Collatos and Monnerat inside her business; the camera was merely another john. In an early scene in Lapa where she opines on a property claim from the former owners of her succulent ‘restaurant,’ Luana whips out a hand fan—the international sartorial symbol of courtesans—and begins flitting it relentlessly. “Talking about these issues got me hot,” she sighs. Then, she breaks the fifth wall to acknowledge the façade she herself has built to toy with the directors. “I’m lying,” she laughs. “I opened the fan because it’s charming.” The girls also possess their own documentary filmmaking equipment: their phones. They status update and broadcast to their hearts’ content, outing a married john or two on Facebook Live along the way.

There was no other option; I went to the wall for Lapa, outing myself to my colleagues in the process. I can still recall the debates where I gently pushed back against several screening committee members who deeply felt the work was defamatory. The whore in me reached a tipping point when the endless conversations about this film began to mirror the rhetoric that is used to silence sex workers’ voices today: that, despite being some of the strongest people, we lack the fortitude to stand up for ourselves. And even when we are brazen and reckless enough to share our experiences with the general public, our words are seen as being the protestations of the unliberated. Or, worse: they are exploited to benefit the platforms of those who have never bought, sold, or even truly enjoyed sex.

Which to say: I can speak to this familial ecosystem of prostitutes, its ferocity, its never-ceasing chatty-ass peanut gallery, its shared resources, and—yes—its tolls. The utility bills begin coming in Queen of Lapa from its first interview in the scene I mentioned. Naturally, this brings me back to New York and the spaces I desire my communities to maintain and create in the near future. How too will those be threatened as we find our city in crisis? I feel preemptively ready to fight for them. I know you already know this, but our crisis is not purely financial; it is ethical. It is those with, in a moment of hardship, using what they have to bully those without into subservience and an arbitrary morality.

Speaking of fighting: Several scenes later, we are privy to Brazilian TV news footage of Luana in 2010. She is hustling on Lapa’s streets and a john, over a foot shorter than her, takes her down a dark city street for a rendezvous. Realizing that he does not have any money, she wails on him. Luana does not stop until this fellow who dared to waste her precious time is lying crumpled on the ground. As brutal as it is, I appreciate this territorialism. This visual of the hardened, effeminate ferocity that society and cinema are usually keen on neglecting feels necessary and, ultimately, true. No room for obfuscation or dishonesty these days.

Long story short, NewFest programmed Lapa. Within a few months’ time, it was selected for the festival’s Grand Jury Prize. Not unlike Luana during the heyday of her cabaret career, the documentary has since traveled the world. I feel so validated by this that I want to keep showing up and showing my ass, so to speak, when it feels important. With everything swirling in the zeitgeist right now—the omnipresence of “WAP”’s brothel fantasy, Kamala Harris’s dicey track record on sex work, the narrative and empathetic competencies of the STARZ drama P-Valley—it feels important to let people know what sex workers look like, be they tours de force like Luana or droll little women like me who write about moving pictures. Before we can assert policy, we must assert that we are people.

There is plenty of Lapa to be had in New York. I want my loved ones to know that there are countless working girls in our own city, doing the damn thing, finding and making beauty and caring for others during the hardest of times.

Hopefully, I can approach this crisis of art and bodies like Luana: unflappably and with plenty of charm.

Wishing you prosperity and beauty among this year’s ashes. Don’t you dare leave New York.

Kisses,

S

09.07.2020

Dear Sarah,

I feel compelled to start my letter to you in response to the last line of yours: Don’t you dare leave New York.

How dare you. I’d never. I grew up close to the city, in New Jersey, and have lived in Brooklyn since I turned 18—which makes 2020 my lucky 13th...

I have some years on you here. I’ve had stints elsewhere—L.A., Amsterdam, Barcelona, and I’d love to have more, maybe in Mexico City, Berlin, maybe São Paulo. I’m thinking of Brazil after reading your thoughts on Queen of Lapa.

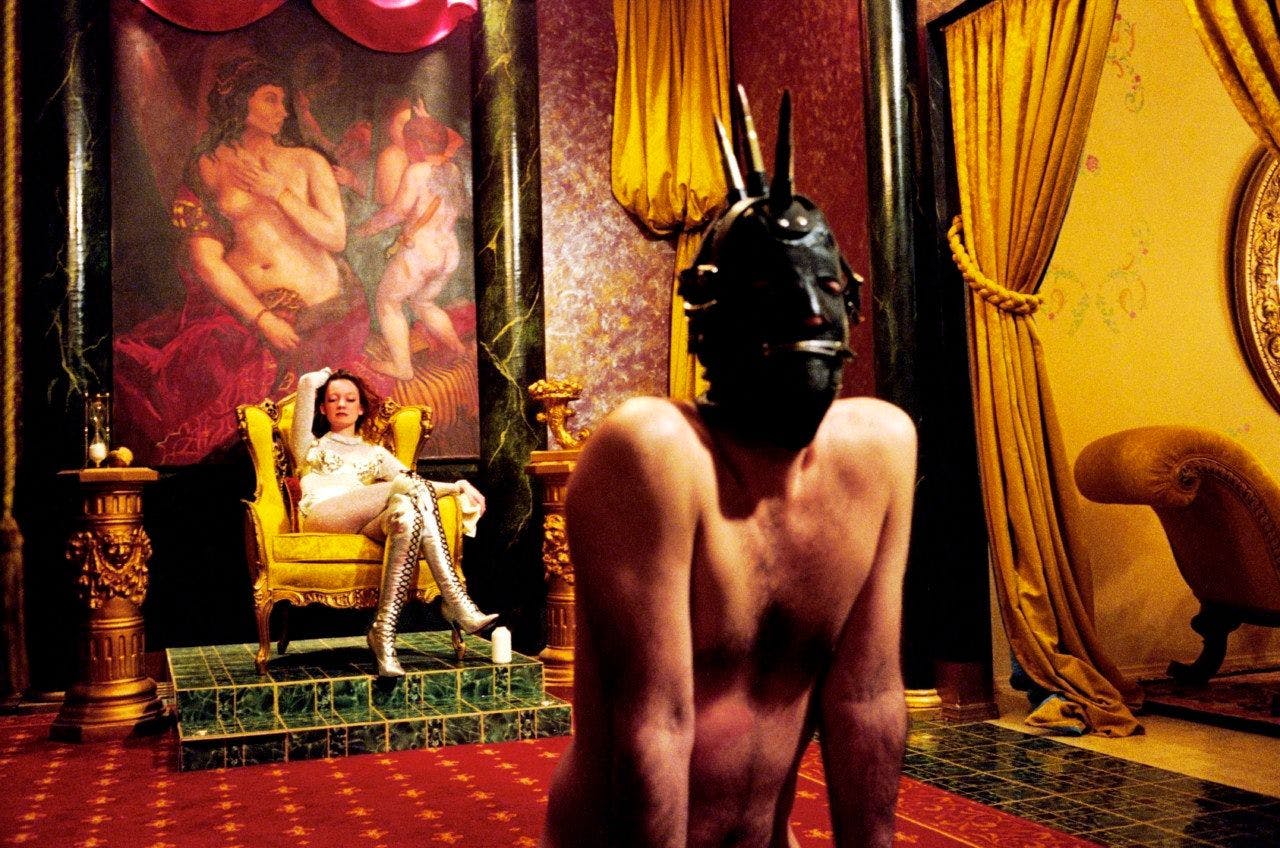

But we aren’t allowed to leave. The borders have been closed, and while domestic travel is still allowed, I haven’t even been on the subway since March. You brought me to another city in your letter, but I will keep you here, in New York, and bring you to Pandora’s Box, the high-class S&M dungeon at the center of Nick Broomfield’s 1996 documentary Fetishes.

I saw this film about 10 years ago, as I descended into the underground myself. I didn’t work at Pandora’s but a similar space in the Garment District. Pandora’s still exists, by the way, but I wonder what’s happened to it during the pandemic. How are brothels, dungeons, and massage parlors weathering this? Will they be around when this is over? And in what form? Sex work is adaptable; it only gets pushed into different forms, venues, corners of the city—it’s never stamped out. It’s too vital. But very few sex workers I know are doing well right now.

I had a recent conversation with a friend who is down to her last dollar. I will help her and there are mutual aid funds, but it’s bleak. I am ready to fight, like you. As I write this, I am thinking of Samuel Delany’s book Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, about the sex industry and porn theaters of the heyday of the Deuce and their planned extinction to usher in what Times Square is now, what Times Square was in March. As of last Thursday, Times Square is just another site where a car drove into protestors.

Fetishes opens with tours of the dungeon space, introductions to various S&M practices, and some frustrations with Broomfield’s presence. The mistresses are cagey around him at first. There is a distinct and high-stakes relationship that sex workers have with revealing and concealing: you always run the risk of getting hurt, of not being in charge of the performance you’ve worked so hard to create and maintain. What was it that you wrote on Instagram ahead of this epistolary exchange?

We have to be in charge of the spectacles of ourselves.

I am thinking of Luana’s fan.

In addition to revealing and concealing, sex workers have a complicated relationship with loneliness and community. I see it in Queen of Lapa, and I have seen it in myself—feeling connected and alienated all at once, feeling totally reliant on others and totally independent. Out on a limb even in loving arms.

I want to relate this sort of loneliness to artists and filmmakers—to how artists want to hide and speak at the same time—but the comparison only goes so far. We are talking about discrimination and social stigma here, and the artist class, while a class of its own, is completely interwoven with other class values. I suppose this is also true of sex work: there’s “survival sex work” and sex work with more agency; sex work moonlighting; and the worlds between Black trans sex workers and girls like myself. It’s understanding the difference between generational poverty and being “broke” but with safety nets. But between Backpage shutting down and the pandemic, I worry about sex workers everywhere, from São Paulo to New York.

In one interview in Fetishes, a dominatrix muses on the difficulties of having romantic relationships while doing “the work.” She says that people get scared. That they don’t understand. I know this wreckage. I think we all do. The chasm between feeling desired and feeling understood. People also often just treat sex workers like shit. We pose a threat, us girls. This is just one of the reasons our connection and correspondence is so compelling, Sarah—a romance between dyke working girl writers. It’s something that Fetishes lacks. The film doesn’t go into the relationships between these working women, save for some very delicious scenes featuring the mistresses and their femme/lesbian submissives (who are also often sex workers themselves). Broomfield acknowledges that these are the sessions that the mistresses seem to enjoy the most.

The connections among sex workers, among queers in NYC, are all closer than they seem. We exist in a continuum of queerness, and in a continuum of whores. I used to know one of the femme submissives in Fetishes, Maria Beatty, a cult lesbian pornographer. She made a couple of infamous black-and-white porn films on 16mm, The Black Glove and The Elegant Spanking, with soundtracks by John Zorn. I was in a film of hers years ago, not porn but an independent feature that devolved into interpersonal drama on set. After that she asked me to make porn in Paris with her. I wanted to, but the money was unclear and it didn’t pan out. Seeing Maria on film now feels like passing someone on the street whom you used to know.

When Broomfield presses the mistresses for more, their walls come up. His misunderstandings and naïveté seem to represent the larger world. It makes his presence in the film critical. Fetishes is not a love letter; it's time spent observing someone. I think this is why some documentaries are more palatable than their subject matter, more clinical than emotive. I wouldn’t use the term “male gaze” here, but more broadly, the gaze of any outsider into sex work is probably more relatable to wider audiences than, say, a documentary on sex work made by sex workers.

I am imagining the possibilities here, and recalling what I am most nostalgic for during this pandemic: the feelings that I had while doing sex work and making experimental film––of independence, touch, slipping in and out of rooms, the type of risk that this isolation has rendered impossible. And the cash from sex work enabled me to make my film, so the two are linked for me in practical ways.

Broomfield lingers on Mistress Raven. After a long career as a pro-domme herself, she opened Pandora’s Box. The domme in charge of the dommes. She’s got jet black hair and looks like the fetish version of a well-dressed Upper East Side woman––a true New Yorker in tailored skirt suits. She doesn’t allow him to film a session of hers. She says she has stopped having sessions, although she offers one to Broomfield. She tells him:

I think that’s totally outrageous, that you can do a documentary about something that you’ve never experienced firsthand.

In her simple refusal, Mistress Raven gets to the heart of art-making and identity politics—to the camera’s ability to capture something it doesn’t own, a specter ever-present in documentary and nonfiction genres. Broomfield presses Mistress Raven on why she no longer has sessions. She talks about being burnt out, about it flooding her life, personally, socially, everything-ly… This is why Raven opened Pandora’s, because she was exhausted.

I appreciate that Broomfield decided not to be completely invisible. His voice and presence get less performatively neutral throughout the movie And the mistresses let him film more; he even captures some of the johns. Eventually, the mistresses have enough of him being coy and chase Broomfield around with a bamboo cane as film equipment dangles from his neck. They tie him up as he squeals, giggles, and resists. But for him, the stakes are low. This isn’t his life. He isn’t a sex worker; he doesn’t walk around the world as an outsider. He peers in, for a second.

Yesterday one of the mistresses I used to work with sent me a photo of us taken in 2012, in which a corset-clad 23-year-old Jillian sports a pout. I immediately asked myself: how have I changed? How haven’t I changed? How has the world changed? How has it not?

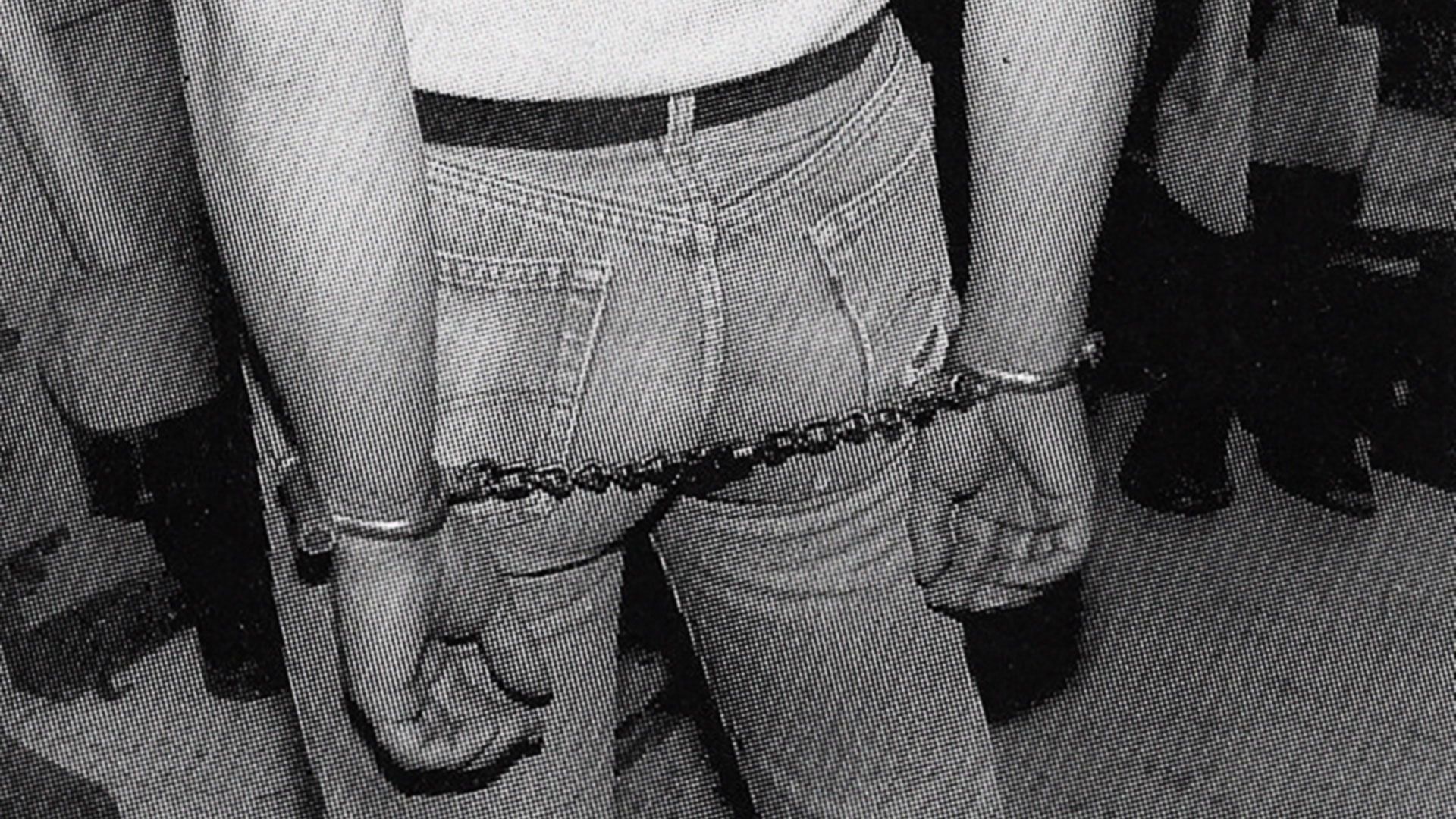

In one of the various sociopolitical S&M sessions in Fetishes, a white cop calls his mistress and confesses to his profiling of young Black men. The bleak reality of his confession stands out to me now, given the events of 2020. All of the stagnation and change we have gone through has melded into a year of loss and revolution. I don’t want to return to normal, even if that was possible. We will have to find new ways to make and watch films, new ways to trick and love.

More soon,

Jillian

***

Sarah Fonseca is a Brooklyn-based film writer whose work has appeared in Condé Nast's them., Fandor, IndieWire, Los Angeles Review of Books, and Museum of the Moving Image's Reverse Shot, among other publications. She has served as a programmer for NewFest and is a member of GALECA, the LGBTQ critics association.

Jillian McManemin is a queer artist and writer whose work has appeared in Hyperallergic, Art Agenda, The Brooklyn Rail, and Art Papers, among other publications. She recently founded the Toppled Monuments Archive and is working on her first book, Sculpture Kills.

Photos courtesy of Theodore Collatos and Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos.