When talking about photographers and cinematographers, we tend to fixate on the quality of their eye — on their unique vision of the world. But capturing images is also an intensely physical, emotional and intellectual activity, of which Brazilian artist Heloisa Passos is a perfect example. Searching for a quiet place to talk in a crowded café, she quickly sizes up the room, gauges the degree to which the ambient music might affect my tape recorder, and installs us in the ideal spot. She’s just arrived for the world premiere at the New York Film Festival of her short documentary Birdie, yet in two days she’ll be headed back to Rio de Janeiro to resume shooting a television series. Passos is a cinematographer for both television and film, fiction and nonfiction, with credits that include Lucy Walker’s Waste Land (nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary in 2011), and Manda Bala (Send a Bullet), for which she won the Outstanding Achievement in Cinematography award at the 2008 Cinema Eye Honors. She’s also a prolific photographer, with numerous exhibitions and monographs to her credit, and finally, as her new films attest, an accomplished director of short works; in addition to Birdie, another new film, Karollyne, is being released this week by Field of Vision. Before the first question could be asked, Passos expressed dismay at the quality of her English but mentioned her affinity for a certain English term. “My accent is not very good,” she said. “But I love this word for making films — observational. Is this correct? Observational. Because that’s the movies I do.”

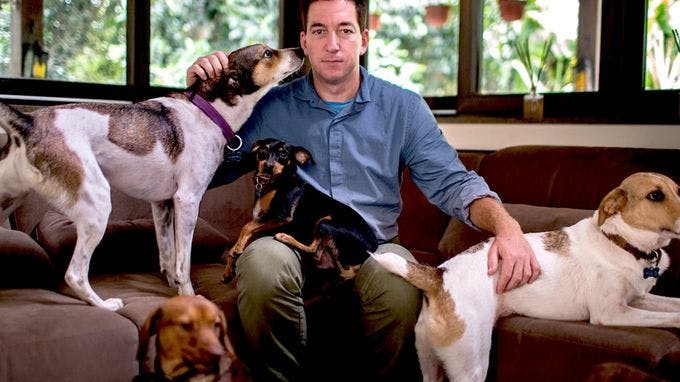

Let’s first talk about how these two films came to pass. Am I correct in saying that Glenn Greenwald came upon this story, the phenomenon of homeless people having deep relationships with animals in Rio, and then the Field of Vision team thought it also could be a film?

Passos: For me it was a very surprising invitation. AJ [Schnack, co-creator of FOV] called me to make a movie about homelessness and dogs. I know that Glenn loves dogs — he has a lot of dogs. So I met him in Rio for the first time, and we went downtown together just to observe people. And then I said OK. I thought it would be important to hire a researcher to bring in some characters, and then we could choose from among them. But also Glenn lives in a very special place in Rio, in a kind of forest. He knew somebody around that forest who had a lot of dogs, but they had never talked. So Glenn went to look for them — I was not with Glenn, my assistant was — but he didn’t find people. What he did find were some dogs and a door to a big house. It had no bell, no way to call people. So he waited for a little bit. It was evening, the night was coming, but then someone finally came. Who came? It was Karollyne. They talked and Glenn became completely impressed by her. One week later the researcher went there during the daylight and sent me footage she recorded. And I said, my god. It’s not only a film about homeless people with dogs — it’s a film about a town, a forest, a community. It’s an occupation. Karollyne was the first one to invade this place, this big mansion in the middle of the forest. She invaded 10 years ago. And then she invited other trans women. It’s so common — in this part of the forest, middle class people go and abandon their dogs. Old dogs, any dogs. And Karollyne and the other people in this occupation, they care about animals, especially dogs.

How did Karollyne feel about participating in the film, and being on camera?

Passos: Karollyne wanted to make a film, but the other trans women didn’t. Karollyne had already served a prison sentence — she was there for four years, but now she’s OK with the government. She’s an ex-con. So Karollyne and this other couple, a straight couple, decided to make the film, out of the 12 people who live in this occupation. On my first day I went there with camera and sound and everything, and it was so complicated. She was very distant, and it was very tough to have a good conversation. The idea was to shoot for two days, stop, and then to come back 10 days later. So during these 10 days between the second and third day of shooting, I would call Karollyne. And she called me. We had a lot of conversations, and we became very close.

What did you talk about?

Passos: About life. About her mother. She left home when she was 11 or 12 — why did she leave her family? In fact she feels that she doesn’t have a family. I mean, a regular family. Her family are her friends in this occupation. We tried to talk a little about the past. I decided not to reference the past in this short film — it’s not about the past, it’s about what’s happening in that moment. But I decided to talk about the past on the phone.

Did knowing about her past affect how you related to each other?

Passos: I think she felt safer. Knowing that I knew her story and respected her. I think she felt safer with me.

Did it affect how you filmed her, knowing more about who she was and what she had lived through?

Passos: In the first few days, she always looked for the camera. Like, “Am I doing well?” Like someone who wants to do it right. Now I didn’t have a conversation with her, like, “I’m going to be invisible,” because the camera is not invisible. The camera is a camera. But what I did on the last day is to share the camera with my assistant. I did the camera on the first and second day, but on the third day I started with the camera before giving it to my assistant. So that I could look in her eyes. It’s hard for me to give away the camera, but I did. Then she was not looking for the camera, she was looking for me. So we made like a triangle. Between the camera, Karollyne and me. And then I got a mise en scene.

You had to sacrifice the camera in order to do that.

Passos: I started with it, then sacrificed it.

Then she was giving to you, and not to the camera.

Passos: It’s so important to understand that.

Let’s also talk about Birdie, the subject of your other film. Did that encounter come after Karollyne?

Passos: No, no. There were four shooting days in a row. Birdie, Karollyne, Birdie, Karollyne. That was the strategy. And then Karollyne I shot again after 10 days. But Birdie only two days — yes, no, yes, no. Because I didn’t want to attack. It was like — brief, then come again. Brief, then come again. Then maybe we’d use a half day for Birdie and half for Karollyne on that fifth day. But we didn’t need to come back for Birdie.

Was he more present and available from the beginning?

Passos: Birdie is a kind of philosopher. He’s someone who really loves to talk. He has a relationship with nature. Karollyne is from Rio, but Birdie is not, he’s from the Amazon. He has a completely different relationship with the town. He’s also an ex-con — they have that in common. But Birdie’s sentence was 12 years. Again I decided that’s not the focus of the film, but I needed to understand this guy to start a relationship with him. Now Birdie doesn’t have a cellphone, and he doesn’t have an address. Our strategy was that my researcher would go every day to the tube station where Birdie goes between 10 to 12 in the morning, and she would say hello Birdie, hello Birdie, on Tuesday you’re going to shoot the film. Then before the first day of shooting, I went to the square where he always goes, and my researcher introduced us. Here’s Heloisa, she’s a friend, she’s going to shoot. Just for 10 minutes the day before the shooting. Hello, hello, tomorrow, tomorrow, OK, now don’t tell me anything. Of course the researcher also went there the day I shot with Karollyne, to confirm with Birdie that he would be there the second day. Because he’s flying. He flies. He really flies.

How did you devise the shots from Birdie’s cart? If you only shot for two days, did you just come up with and execute those shots on the spot?

Passos: When I saw the footage shot by the researcher, I saw the cart. And I thought, I’m going to find a place to set up other cameras. So I used three cameras — a GoPro under the cart, a 5D on the board, and a C-300 for outside shots. But it was crazy. The GoPro, OK, you have small pieces to hold it, but we had only a very small grip, like a suction cup, to use for the 5D camera on the cart. So I showed it to Birdie, and said it doesn’t work on the wood, I need something to suction it onto. And he said, “Give me two minutes.” Then he came back — in two minutes! — with a piece of metal, and we used the piece of metal to suction it onto the 5D. Then I had the C-300 in the car , and for my camera assistant we rented our version of the Citi Bike and she went beside him, just to care for the cameras. Because it was just the first day, Birdie — could run off with the cameras! I needed something to control. So I said to my assistant, “Go with a bike, I’ll go by car, and we’ll try to keep pace.”

But by the second day you knew he wouldn’t make off with them.

Passos: The second day was perfect. We did well. Birdie’s really verbal. He loves to tell stories. It was so hard to cut the footage. Whereas with Karollyne it was really tough. One month before I met Karollyne, her boyfriend died. In our first conversation, she spent an hour talking about the ex boyfriend and about HIV, and about how she also has. It was really tough. It was not a light conversation. She needs to talk, and nobody listens to her. Nobody listens. These are invisible people.