The Bay Area filmmaking team of Katie Galloway and Kelly Duane de la Vega hasn’t exactly parachuted into the zone of conflict between government surveillance and civil rights. It’s a topic they’ve been addressing, in one form or another, for nearly 20 years. Add in the remarkable fact that they’re both children of civil rights lawyers — their fathers were actually colleagues — and you’ve got filmmakers who are deeply immersed in this thorny terrain. Their last feature film, Better This World, told the story of two radicalized Texas friends who became the target of a domestic terrorism sting at the 2008 Republican National Convention. For Eric & “Anna,” they collaborated with The Intercept contributor Trevor Aaronson on a longform article to complement their film. All three talked to Field Notes about the challenges and benefits of crafting a narrative largely (and in the case of the film, entirely) from surveillance material, and of reporting a story for which crucial factual details have only recently been made available — details that call into question the American government’s motives and methods.

Did you originally come together because of a shared interest in these issues — the intersection of surveillance and activism?

Kelly Duane de la Vega: Katie and I met at Berkeley High. We were family acquaintances. Then we both lived in New York on different occasions, both worked as documentary filmmakers, then both moved back to our hometowns and reconnected. Katie had read a New York Times clipping about a couple of activists that got arrested, and there was an entrapment allegation, and we were immediately interested. Within weeks of reconnecting it became our first project. That was in 2009. We’ve been making short to long form documentaries together ever since.

Katie Galloway:: Our fathers worked together as civil rights lawyers, but we didn’t find this out until we worked together. So there’s this history of growing up in the Bay Area in the ’70s and the Black Panthers and SNCC [Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee], which are our cultural roots. My first film on informants was in the mid-’90s, about the use of government informants in the drug war.

Duane de la Vega: I was in the process of working on a piece about John Walker Lindh and was very interested in activism and what is taking it too far, and what happens once you get caught up in the legal system. That film project didn’t end up going forward, but I had a really long-standing interest in that intersection between the government and activism. And then when we made Better This World, it got a lot deeper.

Were you hesitant at all to take on another project in this topic area?

Galloway: For this story, the defense team and the people involved came to us after Better This World because [the stories] were so similar. But we said we couldn’t make this film for a number of reasons, one being that someone else was working on it, but also because we were interested in moving on to other subjects. But it stuck with us. I knew Laura [Poitras] from a long time ago, and we had gone back and forth about the Eric and Anna story for years. So when Eric was released [from prison] I emailed her and said, “Are you interested in doing something on this now?”

Considering how long you’ve been making films in this area, how have you evolved as both journalists and filmmakers over that stretch of time? And would you say those have evolved in tandem, or does one tend to fuel the other?

Duane de la Vega: I think we’re both the kinds of people who are constantly reading newspapers and nonfiction and watching what’s happening. So much has changed [in filmmaking] and we both continued to educate ourselves along those lines and worked on our craft. So in some ways they evolved in tandem and as we’ve grown together as partners.

Galloway: I was raised really in the journalistic model, and did a lot of Frontline [episodes], and so for my subsequent films I’ve been reaching to break free — well not free, but away from a more standard model, towards finding my voice. And I would say Kelly is largely responsible for helping me get there. All of [these films] have been made with no narration, and different storytelling styles that make it much more difficult actually to tell the story. But Kelly and I feel pretty clear that the storytelling we like to do is close to the bone, character-driven narratives with a backdrop that’s huge, that’s at least national but where you can find a very personal way in.

You cover a considerable amount of ground in such a short span of time with this film. My sense of and feelings about both Anna and Eric clearly evolve, and I’m also given a strong larger picture of what it means in terms of justice and government overreach. And yet it’s all communicated through surveillance footage. Was it difficult to manage all of that in just 15 minutes?

Duane de la Vega: It was really difficult because there are layers and layers, and so many options, and the story’s really complicated. But we thought there was power in the surveillance footage in and of itself. That so much of the narrative could evolve from just providing a little window into what was going on. So we tried to pick themes that were representative of the overall picture, and that would allow people to spend time with the characters and get a rhythm of their speech and let them develop, and by doing so paint a portrait of what was going on.

Galloway: When making Better This World we knew that we wanted to make surveillance a character, but we didn’t know quite how it would move and effect people. And so it was quite a natural evolution [on this project] to go, “Why don’t we make it all surveillance?” Leave everything else behind and let the surveillance more or less speak for itself.

I would imagine the editing process for dealing exclusively with surveillance footage was quite different — you’re constructing a story based on what that footage did or didn’t show, on what is or isn’t visible or audible.

Duane de la Vega: Usually it’s a case of trying a lot of different options before you find the right one. That’s the hard part. But once you figure out how you’re going to proceed the stories start to work on their own, and that’s how you know you’re on to something. Beyond that there’s a lot of pre-post — there’s digging, there’s typing up the transcripts, thinking how each will visually play against each other. It was originally developed for Frontline as an hour [-long film], so we had a lot of great stuff pulled. It has to be said of Mike Nicholson, who’s our third producer and graphics editor — we would not be here without him. We would talk with him about ideas and then he would send us back something beautiful.

I like the combination of high and low fi to the film. Graphically, you’ve got typed text and handwritten script, meanwhile you’ve got high-tech surveillance that nevertheless captures pretty cruddy footage. There’s something metaphorically meaningful to that.

Galloway: There’s a quality to these young kids — I mean they’re not kids, she’s a teenager and he’s in his early 20s — there’s kind of a casual, slapdash quality to the whole thing. The scribbled notes, the ellipses and dashes and starting in the middle of things. Here are these young, kind of spacey, not very threatening young people that get presented post-9/11 as someone to fear, as domestic terrorists. And then there’s the style of the FBI’s investigation, where the Ts were not crossed and the Is were not dotted.

You mentioned that Eric & “Anna” was originally intended for Frontline at a longer length. Could you talk about how you adjusted to the shorter length, and what was lost and what might be gained from the adjustment?

Duane de la Vega: Katie and I have produced quite a bit of short format work over the years. We love long format, and we love short format. There’s something really accessible about a short format piece that people can watch at home and on their computer. Obviously with a long format piece there’s a lot of things that would’ve gone into it, probably contemporary interviews and more reenactments. But short form is an incredibly important medium for what we do — it allows us to tell more stories to a wider audience, and not have to crank out a film every three years.

Galloway: You aren’t expected to have all the answers in short form. It sort of unburdens you from this idea that everybody has to have a full picture of everything when they’re done — with the Frontline hour, for example. There are very different standards by which it’s judged. And it’s also lovely to be in conversations with other work.

And with this film you’ve been in direct conversation with Trevor Aaronson’s reporting, which is launching alongside the film for Field of Vision.

Galloway: We worked with Trevor back at the investigative reporting program at Berkeley, where Kelly and I were filmmakers in residence. He wrote a book on post-9/11 domestic security apparatus, taking a broader view.

Trevor Aaronson: I was in the group of fellows that came a year after Katie at UC Berkeley. Katie was still working with the program when she was finishing Better This World, and my focus at that time was on the FBI’s use of informants, specifically the use of informants in stings in Muslim communities post 9/11. Katie was orbiting around the same planet, so to speak, in the sense that she was focusing on the use of informants among left wing political activists. The tactics that the FBI uses are similar in the targeting of both Muslims and left-wing activists. The use of stings, the use of informants.

Galloway: So when we decided to do this story we called Trevor and brought him in to do some of the documents research while we were working on the film — to find out what happened with the government burying, losing or not having these documents. He wrote a first draft and sent it to us, and we were able to add details or flesh things out, and we’ve basically been passing the draft back and forth.

How did you conceive of this written piece as working alongside the film?

Aaronson: Our hope was to try to complement the two as best as possible. I tried to keep a lot of information in the story that would take readers kind of beyond what was in the film. But this was a project that had already been off the ground before I came in. The incredible work that Katie and her team were able to do, getting access to all this video and audio footage that hadn’t been made public before. It gave me the opportunity to work from these videos and tell that narrative. At the same time what I try to do in my story, which is something that can’t be as easily done in a visual work, was to leverage the documents as much as possible. Most of my work is really working with court documents and public records to put together a larger narrative, to give a context to the video, and also explain how it is that a man goes to prison for ten years and finds out that there were 2,500 pages of evidence not provided at his trial. So in some ways there is overlap and there’s no way that there couldn’t be overlap with a written story and a visual story on the same thing. Our hope was that for people who watch the film but also read the story that there won’t be a lot of redundancy, that the visuals and the conversations that Katie used would reveal new things to the person who had read my story and vice versa.

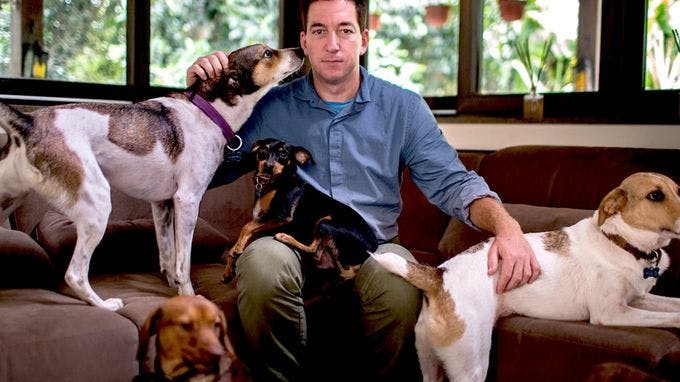

When I talked to Glenn Greenwald a couple weeks ago about the piece that he did with Heloisa Passos, he talked about how film can accomplish certain things more efficiently than writing can normally accomplish, and it challenged him to think of how to use the written piece differently in light of that.

Aaronson: In my story I make the case, I think, that Anna was flirtatious and she was leading Eric on. Now you can describe that in a written story, but when you look at Katie and Kelly’s film, there’s that scene, that visual, of her in the car reaching over and touching him on the leg. And that says so quickly what took me like 1,500 words to explain in the story. There was no way I could compete with that very visceral scene where she does that. So my goal was to say hey, let’s try to tell the whole story of how Anna got in that car. Like this idea that she was just a community college student, even though there’s still this perception that FBI informants are these highly trained people who go undercover. When in truth this was a 17-year-old community college student who the FBI recruited to be an informant.

You’re able to go a bit deeper into Eric and Anna’s stories than the short film can.

Aaronson: I think also it provides an opportunity for armchair psychology on Anna. The wanting to impress the community college professor, then later she has this strange relationship with Ricardo Torres, her FBI handler. A young woman’s desire to impress the older man in a position of authority. You can see how that creates a situation where Anna is potentially manipulated and manipulating the situation. I felt what I could contribute was this fuller picture, fleshing out the biography in a way. If you wanted a fuller picture of what happened, it really lends itself well to a longform written piece.

Both pieces, the film and the written feature, speak to the importance of having information. There’s a difference between piecing a story together in an investigative sense, and repopulating a story after years of its details being intentionally blocked.

Aaronson: Right. Unlike other stories that I’ve worked on where the entire story is new and you’re breaking all sorts of new information, this was a story that, since McDavid’s arrest in 2006, had been substantially reported. I think what we were able to do was take the new information, and take what was out there already, and put together a story that is as definitive as possible. There are also a lot of questions that still exist about why this evidence went missing. The government hasn’t come clean, and even the judge, as I mention in the story, has not taken the opportunity to force the government to explain its actions. Basically, the government got away with saying, “We can’t really explain how this happened.” Given that this is a man who spent 10 years of his life in prison, it’s kind of incredible that the government is now saying, “Oops, dog ate our homework,” you know? As I quote Ben Rosenfeld in saying, that’s kind of the opposite of accountability. Eric did stupid things — I don’t think anyone would deny that. But he wasn’t the domestic terrorist the government portrayed him to be.

That’s an incredibly damning line, that this is “the opposite of accountability.” There are still questions, but the nature of the questions have changed. So instead of “what happened?” — we now know what happened — we’re left with the more unsettling question of “why did this happen?” and “why wasn’t this citizen given a fair trial?”

Aaronson: Right — up until recently, it had always just been claims. You know, Eric McDavid claims that Anna led him on and that’s why he did what he did. And even in the prosecution’s closing arguments, they scoff at that and say there’s no proof, there’s only this one letter that we can find. Well, it turns out there were many letters and we now have those letters, and those letters show very clearly that Eric was being led on by Anna. And from the recordings that Katie and Kelly got, it’s clear that McDavid was not the leader of the plot the way the government claimed he was. These are no longer claims — these are things that are facts based on the records that we have. Now the question is, why was this evidence hidden, why couldn’t the government produce it, and why won’t the government explain what orders it gave Anna? Did the government take a 17, 18-year-old girl, and specifically order her to manipulate a 27-year-old through a promise of a sexual relationship in order to make a counterterrorism case? Because that’s the kind of stuff you’d expect on a sleazy Cinemax show. But in reality we hear, “We can’t provide an explanation for how this happened, all we know was this was in the FBI file the whole time.” And I think that’s incredible. The sad thing is I’m not confident we’ll ever get the answers to why that happened.