No one sees the world quite like Dustin Guy Defa. From his warped home movie Family Nightmare to urban fables like Person to Person and Bad Fever, Defa offers instincts and aesthetics that are completely his own. His latest film, God is an Artist, is no exception. Born and raised in Salt Lake City and currently based in New York, Defa contributes to Field of Vision what he considers his first proper documentary. The day before the FOV launch at the New York Film Festival, we sat down to talk about his approach to the form and the ideas that fueled the film.

How did this film come about? Was the idea something you brought to Field of Vision, or did the producers assign it to you?

Defa: I don’t know whose idea it was, but it was something they wanted to make a film about. I initially thought, that sounds very interesting — I like Shepard Fairey.

Only initially? Then what happened?

Defa: Then I started getting further into it, and realized that while a different filmmaker would be able to make something interesting about that story, I’m not that filmmaker. It was going to be very hard for me to make an interesting documentary about just that subject matter. I don’t know why. I just felt that I would have to do something more investigative than I think I’m capable of.

Or is it also that you’re not as interested in working in that mode?

Defa: Yeah. The story itself, with Fairey’s felony charges — I struggled very hard to think about how I was going to make a movie that I would like that would be about that. I didn’t know how to tell any kind of story inside of that idea. I’ve never made anything like this, never made what would be considered a traditional documentary at all. Now, I’m very interested in street art and grew to have a big appreciation for it as an art. But the thing that was drawing me into the whole thing the most was this manifesto that he had written. And that manifesto started driving me towards something I wanted to make. For a moment I thought I was going to make a movie that could be an offshoot of the manifesto. But part of the manifesto was about frustrating or confusing the spectator, and I wasn’t interested in doing that at all. Meanwhile, I was continually keeping track of what was going on in Detroit, and then the Satanic Temple thing popped up as a news item. It was small at first and then grew into, I think, national coverage. Which I was disappointed about, but by that time I’d gotten my head into it too much to back out.

And so you knew going into shooting the film that these two things, the manifesto and the Satanic Temple, were going to be central?

Defa: Until I was almost finished editing I still thought maybe I was a fool for trying to connect the manifesto to the Satanic Temple. It seemed very difficult. And before making the movie I was thinking the only way I’ll be able to make this kind of movie is to do it the Ross McElwee way, to narrate it throughout. But then when we started shooting I thought, wait — I don’t need to narrate it, I’ve got it. So the first half of editing was without narration, and it was frustrating. So then I finally got back around to narrating.

You became a real thread.

Defa: And I was able to explain my thoughts about how these two things were connected. I couldn’t connect them just through the footage. I had to narrate it to connect things.

How long were you in Detroit? And how did you select what you were going to film?

Defa: We were there for five days. When we got there I was a little bit afraid because I only had one interview set up. I did have a conversation with AJ Schnack in which I said, “Look man I’ve never made a documentary before, is this really how it feels?” I’m not a control freak necessarily, but there’s direction to my direction when I’m making a movie. In this case I wasn’t in control. I was accepting that feeling and I was excited about the idea of not having control over these characters, but I said to AJ, “Is this how it usually is, are you really going in basically blind?” And he said that’s just part of the documentary process. But I had ideas, at least atmospherically, about what I wanted to shoot. Like in the church. And I had a map, but the map was very flexible. We just discovered things as we went.

What did that discovery entail? Did you drive around the city a lot?

Defa: Some driving around, and definitely brainstorming about what we should shoot outside of the interviews. I was filling it in while we were going. Just trying to cover everything. By the time we were ready to leave I did think, OK, I really don’t have anything more to shoot.

You said you didn’t want to incorporate the aspect of the manifesto that makes the audience uncomfortable, which makes me interested in what your limits were, how much you were going to let the film embody the idea of resistance. You discuss resistance quite a bit in the film, and how much you identify with it, but how much was your film going to represent it?

Defa: I don’t feel the film necessarily does. There was a moment where I was like, god it would be great if I could make a movie that resisted against the form of the documentary. I did think about what I could do formally to do that, but this wasn’t that movie. I think maybe I’ve done a little of that with Family Nightmare, but it didn’t seem like a solution for this movie. This actually seemed like a bigger challenge, in a way, to try to make something traditional. I mean, think it’s pretty traditional. It’s a little bit off — it’s not just talking heads, and I’m a character in the movie. But that’s still pretty formally traditional, at least these days.

Other than the connecting of these two main ideas, what else were you trying to bring to the film with your voiceover?

Defa: Going into this movie I was thinking — how do documentarians not put themselves into the movie? If you don’t see or hear the filmmaker, can you feel them? Do you know they’re living in this movie, or are they far away from the movie? I was feeling that as a filmmaker the only way I could make a good documentary was to be very close to the movie. And I was going in very worried about that. Like, what’s going to happen if I’m not close to the movie, because I’m not spending a lot of time with these people. I’ll only have five days in Detroit, and I’ve never been there. How can I be close? But I got there and did feel close in a way. And though I thought about not using narration, that’s ultimately what I needed to be close to the movie. I don’t know how it feels to make a film that’s very straightforward, that’s about a subject matter. It’s not something I can do, I think. Maybe it’s just me wanting to be somewhat in control, so I have to be a character.

But you also have another strong voice in the film, in the form of a character you found on the ground.

Defa: Going in, I thought that in order for the film to work, I was going to have to find a character to voice some of my feelings. And that’s where this Rob guy came in. And that’s just movie magic, when you’re looking for something and that person just shows up. I think he appealed to me because there was something initially different about him, and I needed something different than everything else. But also we’re alike in some ways. And he said a lot of things that would have been great for the movie, about rebellion, resistance, the Satanic Temple, religion. And it’s all so good. But I just needed him to be a bookend, a thread.

Do you think about making another documentary now that you’ve made this one?

Defa: I’d always wanted to, but never realized how I would make one. It makes me more interested, and I also feel more capable now.

How do you feel about being part of Field of Vision?

Defa: I love that they’re giving filmmakers so much freedom. There are limitations — there have to be in order for it to feel that these are assignments. But it’s weird that they chose me. In a way it doesn’t make sense. It’s a risk to have chosen me. It being such a high-profile thing, it being very documentarian, and I’ve never made a documentary, not really. But it also makes me very interested in finding out who else they might choose. I’m very excited that this is what they’re doing, that they’re choosing someone like me.

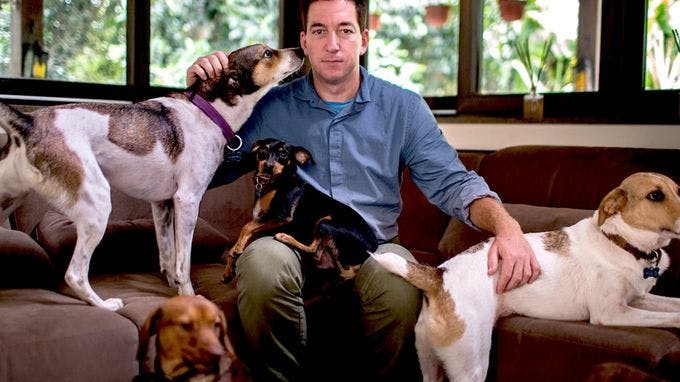

Photo: Scott Macauley