“Hall is the starting point, even the terrain itself, for so many of our intellectual enquiries but a figure who is not always acknowledged and recognised, as such. An intellectual palimpsest that others write from and over, even if they are not aware that they are making their own arguments from positions that Hall himself first formulated and refined.” —Ben Carrington, 2019

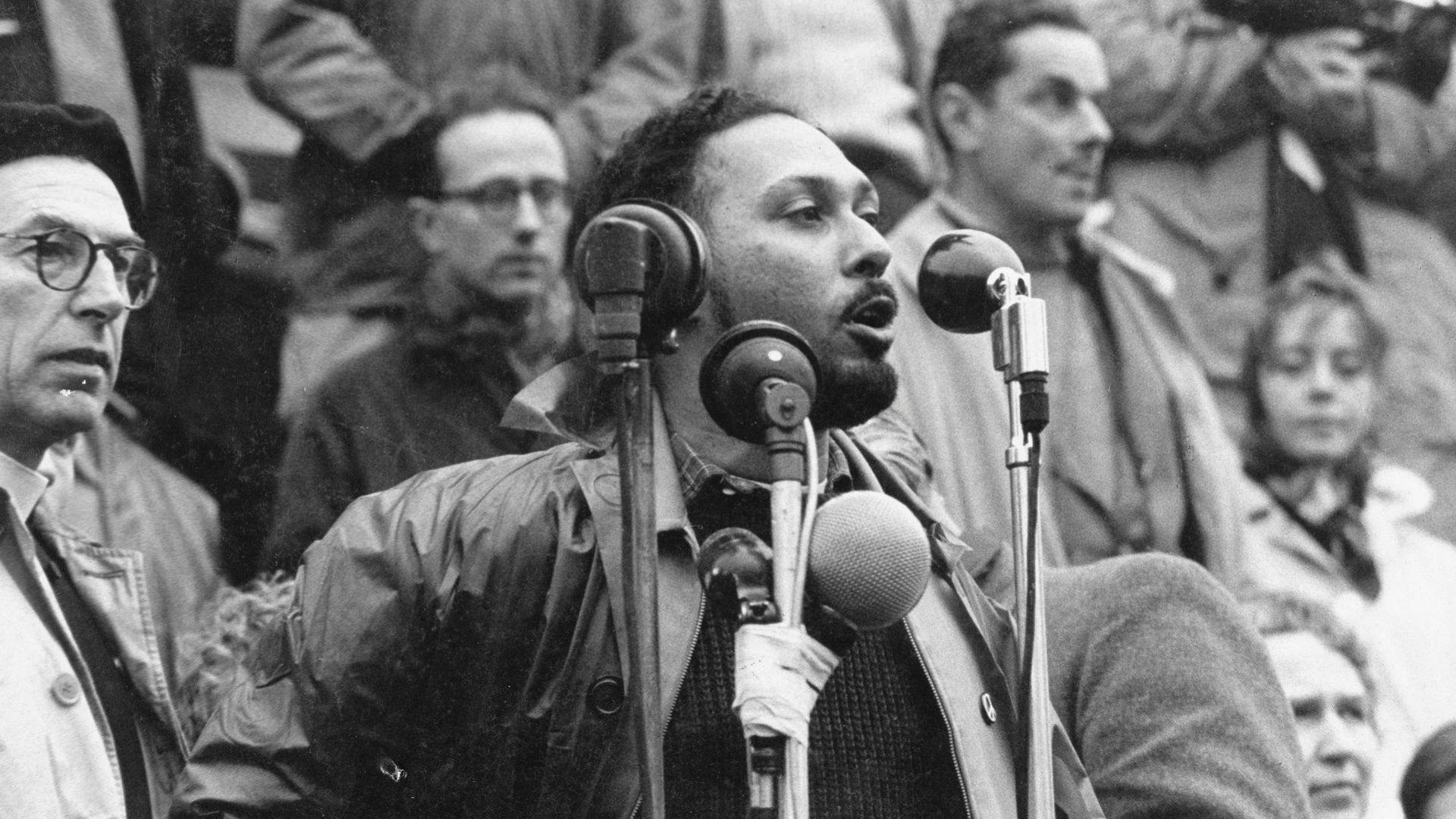

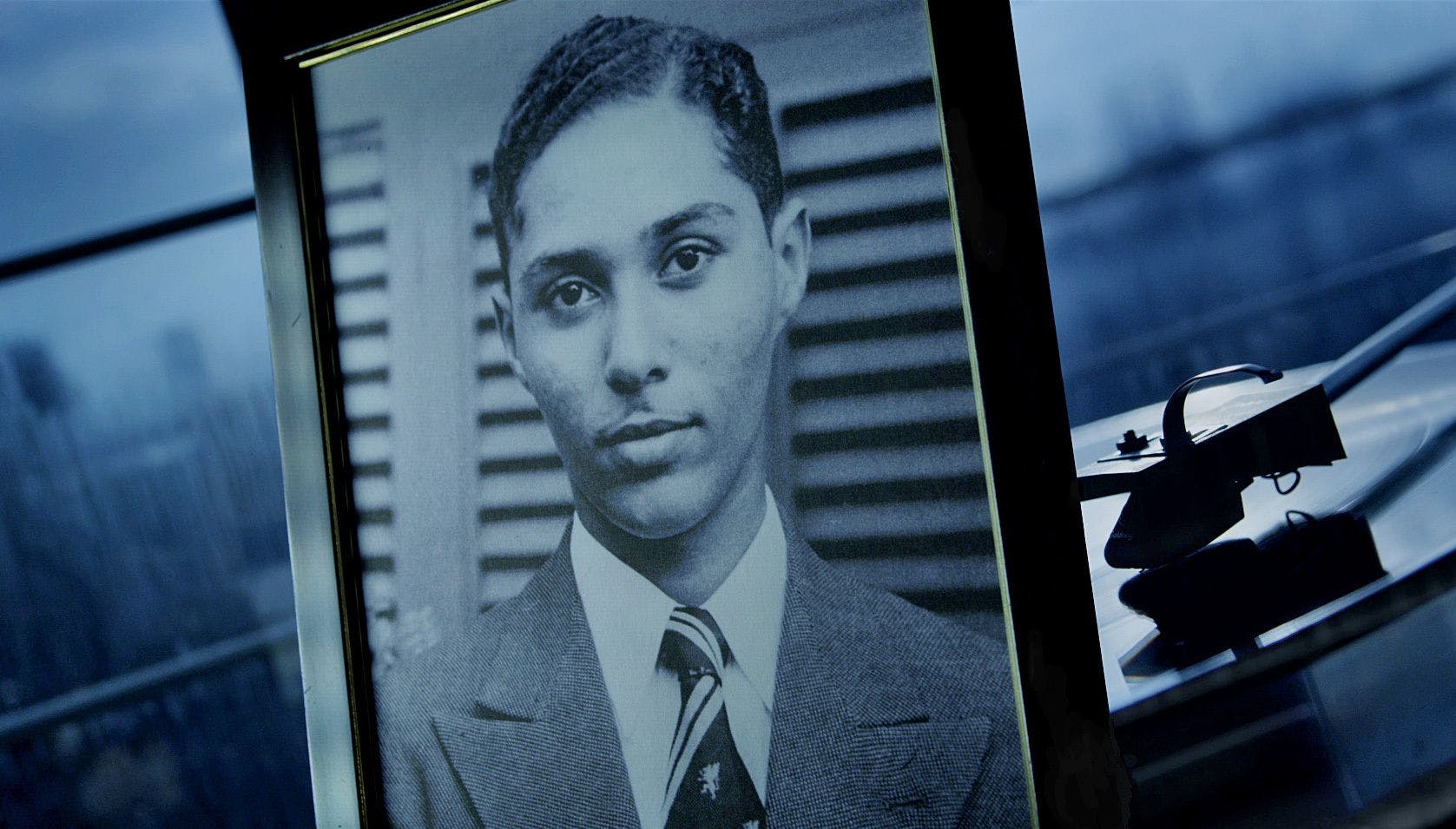

I’ve taken the opportunity during this long coronavirus lockdown period to reacquaint myself with the film- and video-related work of Stuart Hall, the charismatic Jamaican-British polymath. Hall (1932-2014) was a public intellectual, cultural theorist, Marxist sociologist, and co-founder of the New Left Review, who, across a nearly six-decade career, was driven by a desire to complicate staid notions of identity and challenge establishment-sanctioned ideas of “common sense.” In 1951, aged 19, Hall left Jamaica, then still a British colony, to take up a Rhodes Scholarship at Oxford University. In 1964, he co-authored The Popular Arts, one of the first books to argue for the significance of studying film as a serious art form. The text was an early step in Hall's journey to becoming widely hailed as the godfather of the field of Cultural Studies, and one of the most influential figures in a boom of radical Black British filmmaking in the 1980s. Though perennially genial and quick-witted in public appearances, Hall was deadly serious about the importance of closely analyzing popular culture, which, he wrote in his 1981 essay Notes on Deconstructing the Popular, “is one of the sites where this struggle for and against a culture of the powerful is engaged: it is also the stake to be won or lost in that struggle.”

As a broadcaster, Hall placed himself on the front lines of this struggle. In 1979, the year that Margaret Thatcher and her right-wing Conservative government came to power, he played a central role in one of the most remarkable and atypically radical slices of television ever broadcast nationally in the UK. Written and presented by Hall in partnership with the actress and activist Maggie Steed, the TV episode It Ain’t Half Racist, Mum—its name a riff on It Ain’t Half Hot Mum (1974-81), a deeply dubious British sitcom set partially in India in World War II—screened on BBC2 on the 1st and 4th of March 1979. The show was part of Open Door (1973–1983), an experimental series in which the BBC broke with its own tradition and handed over airtime to members of the public, and therefore often marginalized groups, to use under their own editorial control. The “members of the public” in this case were Hall and Steed, who made the program alongside their colleagues from the Campaign Against Racism in the Media (CARM), a pressure group of TV professionals and media scholars. It Ain’t Half Racist, Mum was the 161st edition of the Open Door program, but it was, according to co-writer and co-producer Carl Gardner, “the first programme to address itself critically to television itself, and to the BBC in particular.” [1]

Shot in the style of a standard news broadcast in a black box studio, It Ain’t Half Racist, Mum intercuts tight shots of Hall and Steed (both, it must be said, nattily dressed) addressing the camera with the footage they examine. This sober formal approach is calibrated to make its presenters’ words and faces the focus of our attention. They enunciate crisply and with bite, flying in the face of a long-established British media tendency to obfuscate and traffic in the passive voice, particularly when it comes to matters of race and class. Steed sets a tone of clarity in the show’s opening moments which never flags: “When the BBC says that a program like this is ‘outside their control,’ what they’re telling you is that they don’t think it’s balanced, neutral, or fair. We hope to show that many of the programs which are under the editorial control of the BBC and ITV are themselves biased and unbalanced, especially in the coverage they give to Britain’s Black community.”

Riveting from start to finish, It Ain’t Half Racist, Mum puts into practice Hall’s pioneering “encoding/decoding” model of analyzing television production as a series of codes and signs that are constructed to relay specific messages. Hall and Steed deconstruct a succession of shows, from sitcoms to current affairs news programs, and expose the often racist biases underlying supposedly harmless stereotypes. A passage about the ITV sitcom Mind Your Language (1977-86) explores how its Asian immigrant characters are represented as simultaneously over-industrious, work-shy, and too ill-educated to understand trade unions. “The British Empire was no joke for those on the receiving end,” says Hall. “It’s because of the poverty the Empire left behind that so many Asians and West Indians accepted invitations to come here after the war for work.” Later passages dissect the insidious ways that far-right nationalists, including the infamous Enoch Powell, are given freedom within purportedly neutral spaces on television to articulate their hostile positions on immigration and effectively frame the ensuing discourse on a national stage.

It Ain’t Half Racist, Mum covers plenty of ground, but it can only do so much. As Hall intones in his closing volley, “we haven’t even touched on foreign coverage, the whiter-than-white coverage of the police, the employment of Blacks in television, Black culture, or news bias in press and TV. We believe these issues should be raised in mainstream television programs. But will they be?” Hall, you suspect, already knows the answer. With bone-dry humor, he utters, “I guess this is where we hand editorial control back to the BBC,” as the camera cuts for the first time to a wide shot. The lights and the sound fade, and Hall and Steed engage in a deadpan parody of chummy newscaster badinage. In one final, subversive flourish, the closing credit crawl, instead of listing production staff, names and shames no fewer than ten producers and rights holders who refused Hall and Steed access to material. Following a quietly lethal build-up, it’s a devastating coup de grâce.

So what happened next? Did It Ain’t Half Racist, Mum prompt a period of self-critique and reflection for the legacy broadcaster? Hardly. Severely rattled and under pressure from the prominent (and lawyered-up) journalists Robin Day and Ludovic Kennedy, who were both targets of the show’s reasoned criticism, the BBC, ahead of a later Open Door episode, broadcast an apology-cum-capitulation so total, so utterly feeble, that it is worth repurposing in full:

“The BBC regrets that the Open Door programme broadcast on the 1st and 4th of March this year, by the Campaign Against Racism in the Media, could be taken as implying that Mr. Robin Day had conducted a program about immigration with a racist bias. The BBC considers that any such implication would be wholly unjustified. The BBC also regrets that the Open Door program could similarly be taken to mean that Mr. Ludovic Kennedy had conducted an interview with a National Front spokesman with a racist bias, and that a number of others, named, had presented with a similar bias. The BBC wishes to dissociate itself from any such suggestions which it considers to be entirely without foundation.”

This statement is laughable in its blanket dismissal of specific and well-researched critical arguments in just four panicked sentences. Yet it is an instructive example of a truth that persists today: in privileged institutional circles, to charge someone with harboring or exhibiting racist attitudes is a monstrous, unspeakable crime, more deserving of reproach than actually exhibiting racist attitudes. To this day, the BBC continues to make an ostentatious fetish of political neutrality, while largely maintaining a status quo which empowers whiteness and conservatism, and severely marginalizes the voices of progressive people of color. For one obvious example, consider that Nigel Farage, the far-right politician and key architect of Brexit (responsible for an anti-migrant poster so flagrantly racist it requires no decoding), has appeared 35 times on BBC’s flagship weekly political talk show Question Time. He is the show’s ninth most frequent guest, despite never having been elected to the UK Parliament. Hall foresaw it all.

It Ain’t Half Racist, Mum may not have catalyzed long-term change at the BBC, but a new generation was watching, and Hall became a guiding light for a swathe of Black British nonfiction filmmakers galvanized by his scintillating public presence and rigorous criticism. Black Audio Film Collective, an East London–based group of multimedia artists and radical thinkers formed in the early days of Thatcher’s Britain, was directly inspired by Hall’s analytical approach. Their breakthrough film, Handsworth Songs (1986), was a bracing, collage-like essay documentary about the uprisings which erupted in 1985 in the districts of Handsworth in Birmingham, as well as Brixton and Tottenham in London, in response to racist police brutality and mass unemployment.

Hall was one of the first people to offer feedback on Handsworth Songs during its production. “I was really struck by this man who we were all in awe of. None of us had met him,” said director John Akomfrah in a 2013 interview at London’s ICA Cinema. “We invited him to come and have a look at this film we were making ... We were shocked that he even said yes!” Hall later took to The Guardian’s letters page in 1987 to defend the film from a sniffy attack by novelist Salman Rushdie, who equated its radical form and non-didactic approach with pretension and deemed it “no good.” “[I]t seems to be struggling harder for a language in which to represent Handsworth as I know it than Salman’s lotfy, disdainful, and too-complacent ‘Oh dear’,” wrote Hall. Akomfrah would later direct the elegiac The Stuart Hall Project (2013), which is the place to begin for anyone who wants a succinct yet wide-ranging introduction to Hall’s life and work. The film, a companion piece to Akomfrah’s three-screen installation The Unfinished Conversation (2012), is delicately woven together from over 100 hours of archival radio and television[2] footage featuring Hall, and set to the music of Hall’s favorite artist, Miles Davis.

Black Audio Film Collective’s contemporary Sankofa Film and Video, which formed in the summer of 1983 and comprised five graduates from various London polytechnics and art colleges, was another group directly inspired by Hall. The group's blistering, pugnacious short Territories (1984) used the physical and theoretical “territory” of London’s long-running Notting Hill Carnival as a focal point to explore myriad tensions—class, sex and sexuality, desire, race and racism, labor, state surveillance, and police violence.

Sankofa member Isaac Julien struck up a lifelong friendship with Hall, who narrated parts of Julien’s sensuous Looking For Langston (1989), and all of Black and White in Colour (1992), his excellent two-part documentary about Black representation on British television. Hall also appeared briefly, as a museum visitor, in Julien’s 1993 homoerotic fantasy short, The Attendant, and then as a key onscreen contributor in 1995’s Frantz Fanon: Black Skin, White Mask. I selected this layered documentary about the eponymous French West Indian philosopher, psychiatrist, and revolutionary as the opening night film of the first program I organized in my job at Brooklyn Academy of Music in October 2017. It sold out our largest house (272 seats), and to witness Hall, projected large, addressing a big, diverse crowd in my own place of work, in my adopted country—I was born in London to a Jamaican-British father and a Scottish-Irish mother, and moved to the States in 2014—is among the most moving things I’ve ever experienced in a cinema: a personal moment of bliss where decades of disaporic dialogue seemed to crystallize in a space of communal concentration.

In his obituary for Hall, Julien, now an internationally renowned visual artist, put it plainly: “There is no way of overstating it: I would not do the things I do without Stuart.” Here, Julien is speaking for many of us, and Hall’s presence—cool, calm, analytical, blissfully immortalized on film and video—is as necessary today as it ever was.

***

[1] Amy Villarejo, “Television, Critique, and the Intentionless”, http://www.worldpicturejournal.com/WP_10/pdfs/Villarejo_WP_10.pdf

[2] My personal favorite clips come from the seven-part BBC documentary Redemption Song (1991), a sweeping and complex study of the Caribbean presented by Hall with warmth and wit.

***

Ashley Clark is the director of film programming at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. He has curated film series at BFI Southbank, the Museum of Modern Art, TIFF Bell Lightbox, and the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture, among other venues, and has contributed writing to publications including Film Comment, Sight & Sound, and the Guardian. His first book is Facing Blackness: Media and Minstrelsy in Spike Lee’s “Bamboozled” (2015).

Photos courtesy of Smoking Dog Films.